For 10 years, Ireland’s boom just got “boomier”, in the words of former Taoiseach (Prime Minister), Bertie Ahern. From 1996, house prices rose without a break, pumped with the most potent drug of all : cheap credit and plenty of it. Flimsy financial regulation, tax incentives and soaring numbers of economic immigrants - many of them put to work on construction, thereby creating a vicious circle – ensured that property became the dinner party staple of the era.

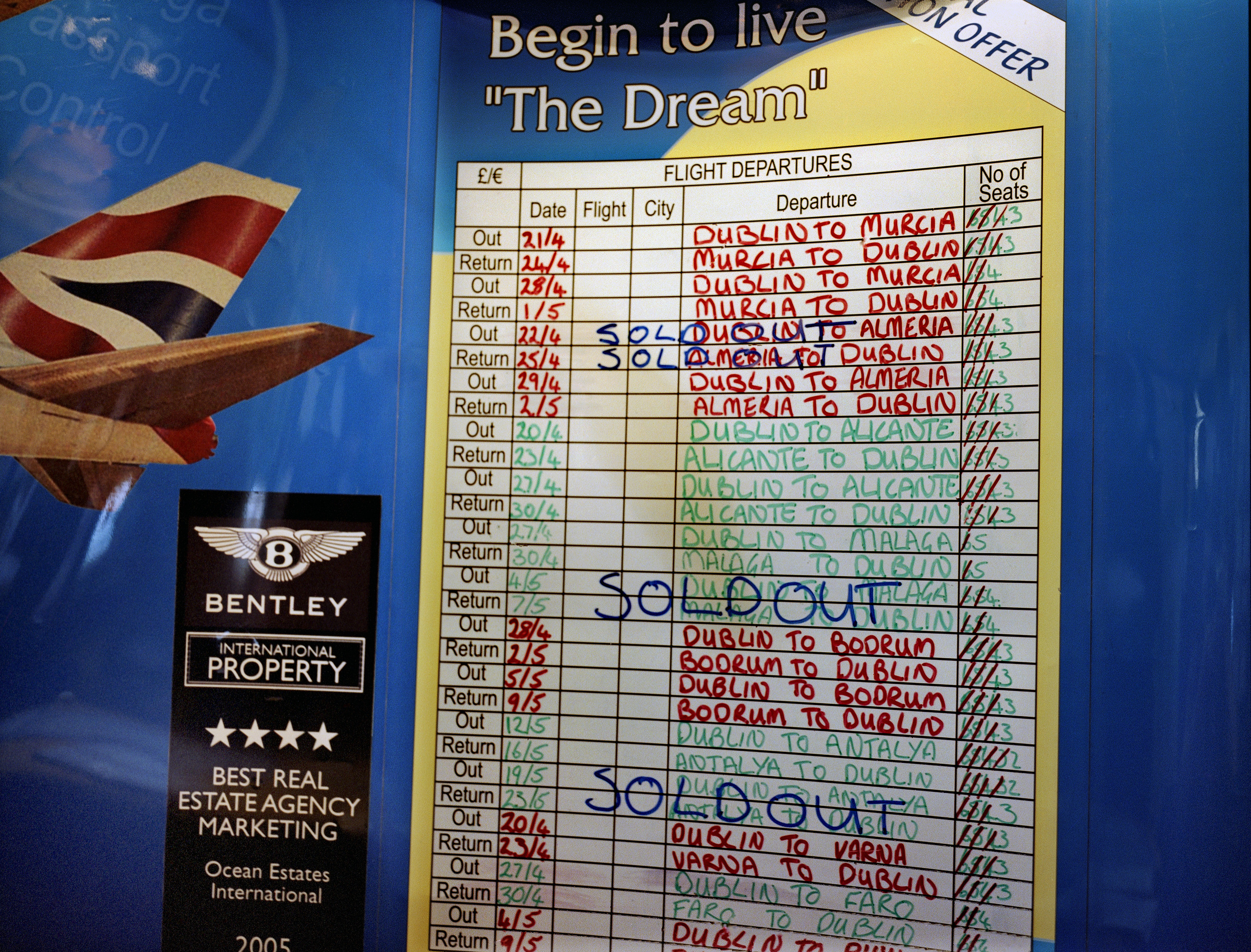

An unholy alliance of builders, developers, estate agents and bankers became the new gentry, mad with hubris, prospering in a culture of greed masquerading as entrepreneurship. Their conspicuous lifestyles - trophy homes, multiple holiday villas, yachts, helicopters and the occasional private jet - were not only accepted, but admired as the well-earned fruits of their buccaneering labours.

At government and local level, politicians facilitated the developers, riding roughshod over planning principles and re-zoning parcels of agricultural land in areas unfit for development. Landowners became multimillionaires overnight, as the builders moved in to throw up insanely over-priced suburban-style houses in rural locations, all of it . financed by bankers driven by rivalry and minimal oversight.

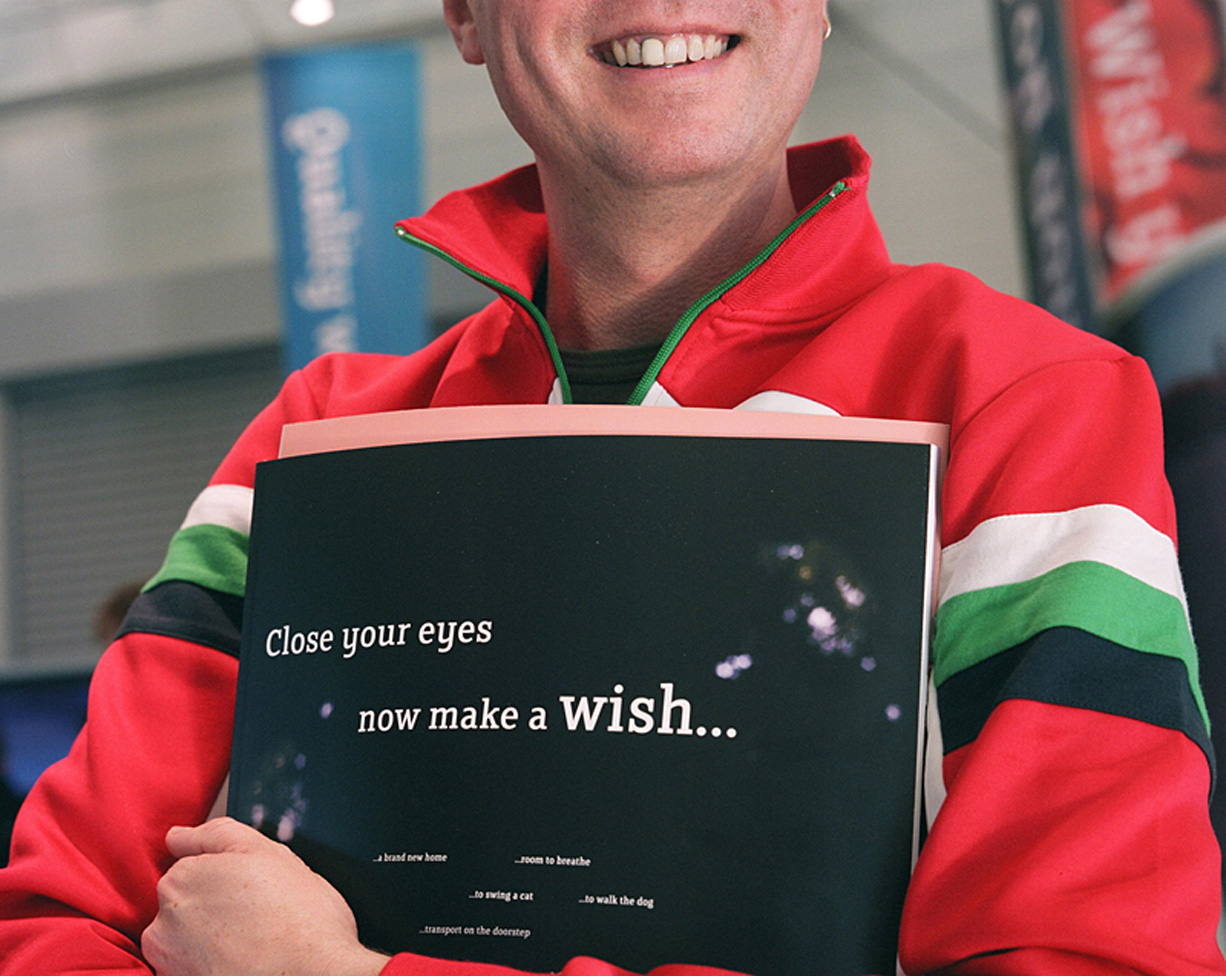

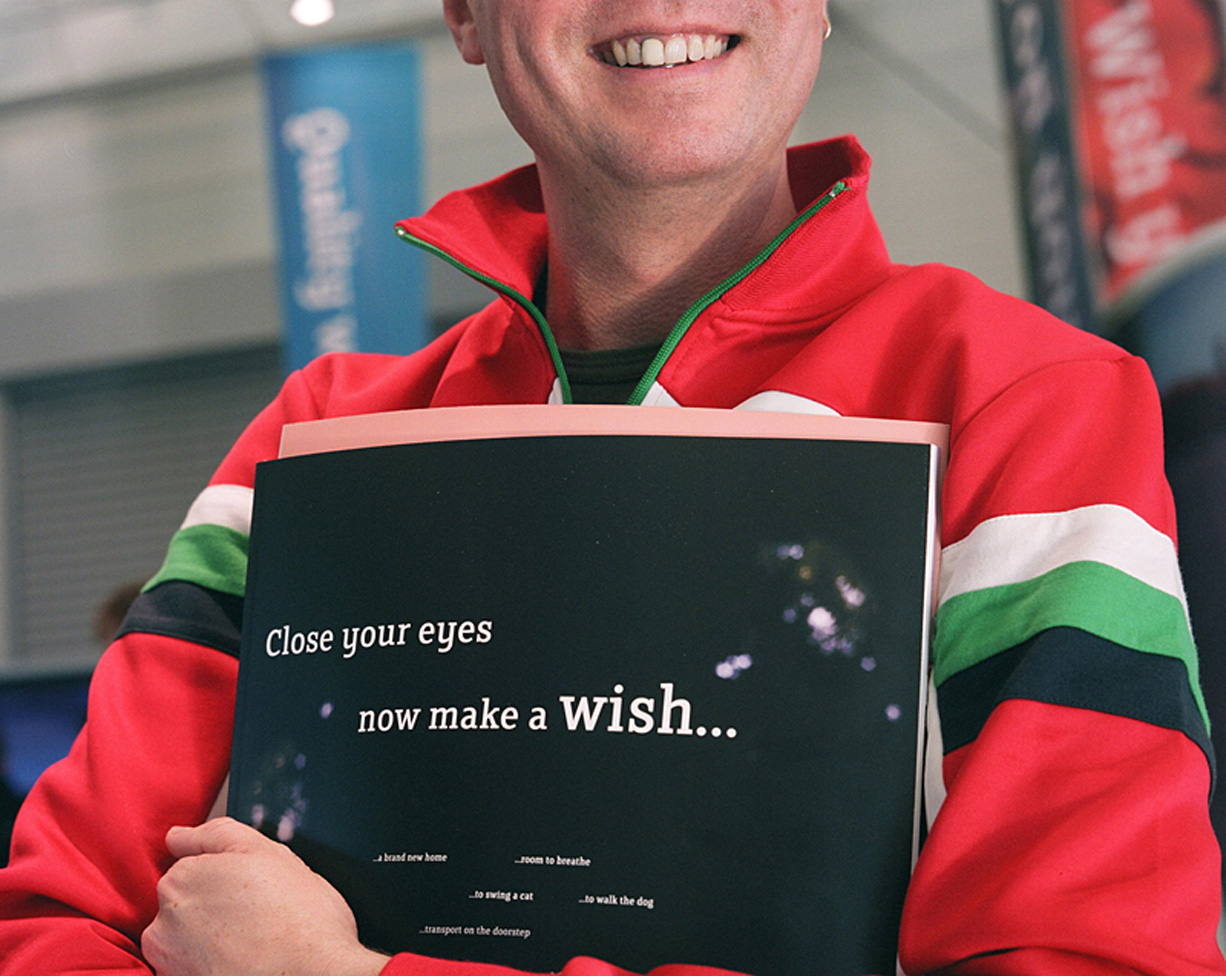

Developers never had to worry about turning a profit, thanks to extraordinary house inflation, fast becoming a bubble. As desperate young couples were forced further from the city for affordable homes and overnight queues became a common feature of new home launches, agents and developers found new ways to milk the frenzy. Where before, phases one and two of a development might be a year apart, the greed fest reached a pitch where an apartment advertised at 270,000 on a Thursday morning could be hiked to 295,000 in a so-called “Phase 2” that same afternoon. Between 2000 and 2007, residential mortgage lending surged by more than 300 per cent - from 29 billion to 123 billion.

The disease was contagious. In the 10 years from 1996, as the Dublin region saw a 366% rise in property values – from an average of €82,400 to €384,247 - many with modest homes in the most non-descript suburb came to believe they were sitting on a goldmine and borrowed gleefully on the strength of it. Some came to fancy themselves as property “experts”. An age of insanity was distilled in one court case in early 2009, where it emerged that a Dublin father of three on an Air Corps pilot’s salary of 53,000 (euro), had managed to build up a twelve-house property portfolio, with loans of 8million euro from nine separate financial institutions.

The common belief, it seemed, was that cheap credit and immigration would last forever. We were invincible. Only a few Cassandras saw the turning in the road. The giddy rise in house prices skidded to a halt when the European Central Bank raised interest rates in 2006 and 2007. Construction sites closed abruptly and tens of thousands of workers were thrown out of work, many of them the immigrants on whom much of the future housing demand relied. Banks and developers on a giddy round of musical chairs were caught when the music stopped. Our crash was even “crashier” – to borrow Bertie’s unique word treatment – than any other country in Europe

The true value of half-completed housing developments on stunningly obscure sites in the so-called commuter counties lies savagely exposed. Agricultural land bought for astronomical sums at the height of the boom are reduced to wasteland. “Zombie” hotels, “ghost” estates and mothballed apartment blocks mock the hubris of another era, like the desert kingdom of Ozymandias : “Look on my works, ye Mighty, and dispair!”.

For 10 years, Ireland’s boom just got “boomier”, in the words of former Taoiseach (Prime Minister), Bertie Ahern. From 1996, house prices rose without a break, pumped with the most potent drug of all : cheap credit and plenty of it. Flimsy financial regulation, tax incentives and soaring numbers of economic immigrants - many of them put to work on construction, thereby creating a vicious circle – ensured that property became the dinner party staple of the era.

An unholy alliance of builders, developers, estate agents and bankers became the new gentry, mad with hubris, prospering in a culture of greed masquerading as entrepreneurship. Their conspicuous lifestyles - trophy homes, multiple holiday villas, yachts, helicopters and the occasional private jet - were not only accepted, but admired as the well-earned fruits of their buccaneering labours.

At government and local level, politicians facilitated the developers, riding roughshod over planning principles and re-zoning parcels of agricultural land in areas unfit for development. Landowners became multimillionaires overnight, as the builders moved in to throw up insanely over-priced suburban-style houses in rural locations, all of it . financed by bankers driven by rivalry and minimal oversight.

Developers never had to worry about turning a profit, thanks to extraordinary house inflation, fast becoming a bubble. As desperate young couples were forced further from the city for affordable homes and overnight queues became a common feature of new home launches, agents and developers found new ways to milk the frenzy. Where before, phases one and two of a development might be a year apart, the greed fest reached a pitch where an apartment advertised at 270,000 on a Thursday morning could be hiked to 295,000 in a so-called “Phase 2” that same afternoon. Between 2000 and 2007, residential mortgage lending surged by more than 300 per cent - from 29 billion to 123 billion.

The disease was contagious. In the 10 years from 1996, as the Dublin region saw a 366% rise in property values – from an average of €82,400 to €384,247 - many with modest homes in the most non-descript suburb came to believe they were sitting on a goldmine and borrowed gleefully on the strength of it. Some came to fancy themselves as property “experts”. An age of insanity was distilled in one court case in early 2009, where it emerged that a Dublin father of three on an Air Corps pilot’s salary of 53,000 (euro), had managed to build up a twelve-house property portfolio, with loans of 8million euro from nine separate financial institutions.

The common belief, it seemed, was that cheap credit and immigration would last forever. We were invincible. Only a few Cassandras saw the turning in the road. The giddy rise in house prices skidded to a halt when the European Central Bank raised interest rates in 2006 and 2007. Construction sites closed abruptly and tens of thousands of workers were thrown out of work, many of them the immigrants on whom much of the future housing demand relied. Banks and developers on a giddy round of musical chairs were caught when the music stopped. Our crash was even “crashier” – to borrow Bertie’s unique word treatment – than any other country in Europe

The true value of half-completed housing developments on stunningly obscure sites in the so-called commuter counties lies savagely exposed. Agricultural land bought for astronomical sums at the height of the boom are reduced to wasteland. “Zombie” hotels, “ghost” estates and mothballed apartment blocks mock the hubris of another era, like the desert kingdom of Ozymandias : “Look on my works, ye Mighty, and dispair!”.

For 10 years, Ireland’s boom just got “boomier”, in the words of former Taoiseach (Prime Minister), Bertie Ahern. From 1996, house prices rose without a break, pumped with the most potent drug of all : cheap credit and plenty of it. Flimsy financial regulation, tax incentives and soaring numbers of economic immigrants - many of them put to work on construction, thereby creating a vicious circle – ensured that property became the dinner party staple of the era.

An unholy alliance of builders, developers, estate agents and bankers became the new gentry, mad with hubris, prospering in a culture of greed masquerading as entrepreneurship. Their conspicuous lifestyles - trophy homes, multiple holiday villas, yachts, helicopters and the occasional private jet - were not only accepted, but admired as the well-earned fruits of their buccaneering labours.

At government and local level, politicians facilitated the developers, riding roughshod over planning principles and re-zoning parcels of agricultural land in areas unfit for development. Landowners became multimillionaires overnight, as the builders moved in to throw up insanely over-priced suburban-style houses in rural locations, all of it . financed by bankers driven by rivalry and minimal oversight.

Developers never had to worry about turning a profit, thanks to extraordinary house inflation, fast becoming a bubble. As desperate young couples were forced further from the city for affordable homes and overnight queues became a common feature of new home launches, agents and developers found new ways to milk the frenzy. Where before, phases one and two of a development might be a year apart, the greed fest reached a pitch where an apartment advertised at 270,000 on a Thursday morning could be hiked to 295,000 in a so-called “Phase 2” that same afternoon. Between 2000 and 2007, residential mortgage lending surged by more than 300 per cent - from 29 billion to 123 billion.

The disease was contagious. In the 10 years from 1996, as the Dublin region saw a 366% rise in property values – from an average of €82,400 to €384,247 - many with modest homes in the most non-descript suburb came to believe they were sitting on a goldmine and borrowed gleefully on the strength of it. Some came to fancy themselves as property “experts”. An age of insanity was distilled in one court case in early 2009, where it emerged that a Dublin father of three on an Air Corps pilot’s salary of 53,000 (euro), had managed to build up a twelve-house property portfolio, with loans of 8million euro from nine separate financial institutions.

The common belief, it seemed, was that cheap credit and immigration would last forever. We were invincible. Only a few Cassandras saw the turning in the road. The giddy rise in house prices skidded to a halt when the European Central Bank raised interest rates in 2006 and 2007. Construction sites closed abruptly and tens of thousands of workers were thrown out of work, many of them the immigrants on whom much of the future housing demand relied. Banks and developers on a giddy round of musical chairs were caught when the music stopped. Our crash was even “crashier” – to borrow Bertie’s unique word treatment – than any other country in Europe

The true value of half-completed housing developments on stunningly obscure sites in the so-called commuter counties lies savagely exposed. Agricultural land bought for astronomical sums at the height of the boom are reduced to wasteland. “Zombie” hotels, “ghost” estates and mothballed apartment blocks mock the hubris of another era, like the desert kingdom of Ozymandias : “Look on my works, ye Mighty, and dispair!”.

For 10 years, Ireland’s boom just got “boomier”, in the words of former Taoiseach, Bertie Ahern. From 1996, house prices rose without a break, pumped with the most potent drug of all : cheap credit and plenty of it. Flimsy financial regulation, tax incentives and soaring numbers of economic immigrants - many of them put to work on construction, thereby creating a vicious circle – ensured that property became the dinner party staple of the era.

An unholy alliance of builders, developers, estate agents and bankers became the new gentry, mad with hubris, prospering in a culture of greed masquerading as entrepreneurship. Their conspicuous lifestyles - trophy homes, multiple holiday villas, yachts, helicopters and the occasional private jet - were not only accepted, but admired as the well-earned fruits of their buccaneering labours.

At government and local level, politicians facilitated the developers, riding roughshod over planning principles and re-zoning parcels of agricultural land in areas unfit for development. Landowners became multimillionaires overnight, as the builders moved in to throw up insanely over-priced suburban-style houses in rural locations, all of it . financed by bankers driven by rivalry and minimal oversight.

Developers never had to worry about turning a profit, thanks to extraordinary house inflation, fast becoming a bubble. As desperate young couples were forced further from the city for affordable homes and overnight queues became a common feature of new home launches, agents and developers found new ways to milk the frenzy. Where before, phases one and two of a development might be a year apart, the greed fest reached a pitch where an apartment advertised at 270,000 on a Thursday morning could be hiked to 295,000 in a so-called “Phase 2” that same afternoon. Between 2000 and 2007, residential mortgage lending surged by more than 300 per cent - from 29 billion to 123 billion.

The disease was contagious. In the 10 years from 1996, as the Dublin region saw a 366% rise in property values – from an average of €82,400 to €384,247 - many with modest homes in the most non-descript suburb came to believe they were sitting on a goldmine and borrowed gleefully on the strength of it. Some came to fancy themselves as property “experts”. An age of insanity was distilled in one court case in early 2009, where it emerged that a Dublin father of three on an Air Corps pilot’s salary of 53,000 (euro), had managed to build up a twelve-house property portfolio, with loans of 8million euro from nine separate financial institutions.

The common belief, it seemed, was that cheap credit and immigration would last forever. We were invincible. Only a few Cassandras saw the turning in the road. The giddy rise in house prices skidded to a halt when the European Central Bank raised interest rates in 2006 and 2007. Construction sites closed abruptly and tens of thousands of workers were thrown out of work, many of them the immigrants on whom much of the future housing demand relied. Banks and developers on a giddy round of musical chairs were caught when the music stopped. Our crash was even “crashier” – to borrow Bertie’s unique word treatment – than any other country in Europe

The true value of half-completed housing developments on stunningly obscure sites in the so-called commuter counties lies savagely exposed. Agricultural land bought for astronomical sums at the height of the boom are reduced to wasteland. “Zombie” hotels, “ghost” estates and mothballed apartment blocks mock the hubris of another era, like the desert kingdom of Ozymandias : “Look on my works, ye Mighty, and dispair!”.

For 10 years, Ireland’s boom just got “boomier”, in the words of former Taoiseach, Bertie Ahern. From 1996, house prices rose without a break, pumped with the most potent drug of all : cheap credit and plenty of it. Flimsy financial regulation, tax incentives and soaring numbers of economic immigrants - many of them put to work on construction, thereby creating a vicious circle – ensured that property became the dinner party staple of the era.

An unholy alliance of builders, developers, estate agents and bankers became the new gentry, mad with hubris, prospering in a culture of greed masquerading as entrepreneurship. Their conspicuous lifestyles - trophy homes, multiple holiday villas, yachts, helicopters and the occasional private jet - were not only accepted, but admired as the well-earned fruits of their buccaneering labours.

At government and local level, politicians facilitated the developers, riding roughshod over planning principles and re-zoning parcels of agricultural land in areas unfit for development. Landowners became multimillionaires overnight, as the builders moved in to throw up insanely over-priced suburban-style houses in rural locations, all of it . financed by bankers driven by rivalry and minimal oversight.

Developers never had to worry about turning a profit, thanks to extraordinary house inflation, fast becoming a bubble. As desperate young couples were forced further from the city for affordable homes and overnight queues became a common feature of new home launches, agents and developers found new ways to milk the frenzy. Where before, phases one and two of a development might be a year apart, the greed fest reached a pitch where an apartment advertised at 270,000 on a Thursday morning could be hiked to 295,000 in a so-called “Phase 2” that same afternoon. Between 2000 and 2007, residential mortgage lending surged by more than 300 per cent - from 29 billion to 123 billion.

The disease was contagious. In the 10 years from 1996, as the Dublin region saw a 366% rise in property values – from an average of €82,400 to €384,247 - many with modest homes in the most non-descript suburb came to believe they were sitting on a goldmine and borrowed gleefully on the strength of it. Some came to fancy themselves as property “experts”. An age of insanity was distilled in one court case in early 2009, where it emerged that a Dublin father of three on an Air Corps pilot’s salary of 53,000 (euro), had managed to build up a twelve-house property portfolio, with loans of 8million euro from nine separate financial institutions.

The common belief, it seemed, was that cheap credit and immigration would last forever. We were invincible. Only a few Cassandras saw the turning in the road. The giddy rise in house prices skidded to a halt when the European Central Bank raised interest rates in 2006 and 2007. Construction sites closed abruptly and tens of thousands of workers were thrown out of work, many of them the immigrants on whom much of the future housing demand relied. Banks and developers on a giddy round of musical chairs were caught when the music stopped. Our crash was even “crashier” – to borrow Bertie’s unique word treatment – than any other country in Europe

The true value of half-completed housing developments on stunningly obscure sites in the so-called commuter counties lies savagely exposed. Agricultural land bought for astronomical sums at the height of the boom are reduced to wasteland. “Zombie” hotels, “ghost” estates and mothballed apartment blocks mock the hubris of another era, like the desert kingdom of Ozymandias : “Look on my works, ye Mighty, and dispair!”.

For 10 years, Ireland’s boom just got “boomier”, in the words of former Taoiseach, Bertie Ahern. From 1996, house prices rose without a break, pumped with the most potent drug of all : cheap credit and plenty of it. Flimsy financial regulation, tax incentives and soaring numbers of economic immigrants - many of them put to work on construction, thereby creating a vicious circle – ensured that property became the dinner party staple of the era.

An unholy alliance of builders, developers, estate agents and bankers became the new gentry, mad with hubris, prospering in a culture of greed masquerading as entrepreneurship. Their conspicuous lifestyles - trophy homes, multiple holiday villas, yachts, helicopters and the occasional private jet - were not only accepted, but admired as the well-earned fruits of their buccaneering labours.

At government and local level, politicians facilitated the developers, riding roughshod over planning principles and re-zoning parcels of agricultural land in areas unfit for development. Landowners became multimillionaires overnight, as the builders moved in to throw up insanely over-priced suburban-style houses in rural locations, all of it . financed by bankers driven by rivalry and minimal oversight.

Developers never had to worry about turning a profit, thanks to extraordinary house inflation, fast becoming a bubble. As desperate young couples were forced further from the city for affordable homes and overnight queues became a common feature of new home launches, agents and developers found new ways to milk the frenzy. Where before, phases one and two of a development might be a year apart, the greed fest reached a pitch where an apartment advertised at 270,000 on a Thursday morning could be hiked to 295,000 in a so-called “Phase 2” that same afternoon. Between 2000 and 2007, residential mortgage lending surged by more than 300 per cent - from 29 billion to 123 billion.

The disease was contagious. In the 10 years from 1996, as the Dublin region saw a 366% rise in property values – from an average of €82,400 to €384,247 - many with modest homes in the most non-descript suburb came to believe they were sitting on a goldmine and borrowed gleefully on the strength of it. Some came to fancy themselves as property “experts”. An age of insanity was distilled in one court case in early 2009, where it emerged that a Dublin father of three on an Air Corps pilot’s salary of 53,000 (euro), had managed to build up a twelve-house property portfolio, with loans of 8million euro from nine separate financial institutions.

The common belief, it seemed, was that cheap credit and immigration would last forever. We were invincible. Only a few Cassandras saw the turning in the road. The giddy rise in house prices skidded to a halt when the European Central Bank raised interest rates in 2006 and 2007. Construction sites closed abruptly and tens of thousands of workers were thrown out of work, many of them the immigrants on whom much of the future housing demand relied. Banks and developers on a giddy round of musical chairs were caught when the music stopped. Our crash was even “crashier” – to borrow Bertie’s unique word treatment – than any other country in Europe

The true value of half-completed housing developments on stunningly obscure sites in the so-called commuter counties lies savagely exposed. Agricultural land bought for astronomical sums at the height of the boom are reduced to wasteland. “Zombie” hotels, “ghost” estates and mothballed apartment blocks mock the hubris of another era, like the desert kingdom of Ozymandias : “Look on my works, ye Mighty, and dispair!”.

For 10 years, Ireland’s boom just got “boomier”, in the words of former Taoiseach, Bertie Ahern. From 1996, house prices rose without a break, pumped with the most potent drug of all : cheap credit and plenty of it. Flimsy financial regulation, tax incentives and soaring numbers of economic immigrants - many of them put to work on construction, thereby creating a vicious circle – ensured that property became the dinner party staple of the era.

An unholy alliance of builders, developers, estate agents and bankers became the new gentry, mad with hubris, prospering in a culture of greed masquerading as entrepreneurship. Their conspicuous lifestyles - trophy homes, multiple holiday villas, yachts, helicopters and the occasional private jet - were not only accepted, but admired as the well-earned fruits of their buccaneering labours.

At government and local level, politicians facilitated the developers, riding roughshod over planning principles and re-zoning parcels of agricultural land in areas unfit for development. Landowners became multimillionaires overnight, as the builders moved in to throw up insanely over-priced suburban-style houses in rural locations, all of it . financed by bankers driven by rivalry and minimal oversight.

Developers never had to worry about turning a profit, thanks to extraordinary house inflation, fast becoming a bubble. As desperate young couples were forced further from the city for affordable homes and overnight queues became a common feature of new home launches, agents and developers found new ways to milk the frenzy. Where before, phases one and two of a development might be a year apart, the greed fest reached a pitch where an apartment advertised at 270,000 on a Thursday morning could be hiked to 295,000 in a so-called “Phase 2” that same afternoon. Between 2000 and 2007, residential mortgage lending surged by more than 300 per cent - from 29 billion to 123 billion.

The disease was contagious. In the 10 years from 1996, as the Dublin region saw a 366% rise in property values – from an average of €82,400 to €384,247 - many with modest homes in the most non-descript suburb came to believe they were sitting on a goldmine and borrowed gleefully on the strength of it. Some came to fancy themselves as property “experts”. An age of insanity was distilled in one court case in early 2009, where it emerged that a Dublin father of three on an Air Corps pilot’s salary of 53,000 (euro), had managed to build up a twelve-house property portfolio, with loans of 8million euro from nine separate financial institutions.

The common belief, it seemed, was that cheap credit and immigration would last forever. We were invincible. Only a few Cassandras saw the turning in the road. The giddy rise in house prices skidded to a halt when the European Central Bank raised interest rates in 2006 and 2007. Construction sites closed abruptly and tens of thousands of workers were thrown out of work, many of them the immigrants on whom much of the future housing demand relied. Banks and developers on a giddy round of musical chairs were caught when the music stopped. Our crash was even “crashier” – to borrow Bertie’s unique word treatment – than any other country in Europe

The true value of half-completed housing developments on stunningly obscure sites in the so-called commuter counties lies savagely exposed. Agricultural land bought for astronomical sums at the height of the boom are reduced to wasteland. “Zombie” hotels, “ghost” estates and mothballed apartment blocks mock the hubris of another era, like the desert kingdom of Ozymandias : “Look on my works, ye Mighty, and dispair!”.

For 10 years, Ireland’s boom just got “boomier”, in the words of former Taoiseach, Bertie Ahern. From 1996, house prices rose without a break, pumped with the most potent drug of all : cheap credit and plenty of it. Flimsy financial regulation, tax incentives and soaring numbers of economic immigrants - many of them put to work on construction, thereby creating a vicious circle – ensured that property became the dinner party staple of the era.

An unholy alliance of builders, developers, estate agents and bankers became the new gentry, mad with hubris, prospering in a culture of greed masquerading as entrepreneurship. Their conspicuous lifestyles - trophy homes, multiple holiday villas, yachts, helicopters and the occasional private jet - were not only accepted, but admired as the well-earned fruits of their buccaneering labours.

At government and local level, politicians facilitated the developers, riding roughshod over planning principles and re-zoning parcels of agricultural land in areas unfit for development. Landowners became multimillionaires overnight, as the builders moved in to throw up insanely over-priced suburban-style houses in rural locations, all of it . financed by bankers driven by rivalry and minimal oversight.

Developers never had to worry about turning a profit, thanks to extraordinary house inflation, fast becoming a bubble. As desperate young couples were forced further from the city for affordable homes and overnight queues became a common feature of new home launches, agents and developers found new ways to milk the frenzy. Where before, phases one and two of a development might be a year apart, the greed fest reached a pitch where an apartment advertised at 270,000 on a Thursday morning could be hiked to 295,000 in a so-called “Phase 2” that same afternoon. Between 2000 and 2007, residential mortgage lending surged by more than 300 per cent - from 29 billion to 123 billion.

The disease was contagious. In the 10 years from 1996, as the Dublin region saw a 366% rise in property values – from an average of €82,400 to €384,247 - many with modest homes in the most non-descript suburb came to believe they were sitting on a goldmine and borrowed gleefully on the strength of it. Some came to fancy themselves as property “experts”. An age of insanity was distilled in one court case in early 2009, where it emerged that a Dublin father of three on an Air Corps pilot’s salary of 53,000 (euro), had managed to build up a twelve-house property portfolio, with loans of 8million euro from nine separate financial institutions.

The common belief, it seemed, was that cheap credit and immigration would last forever. We were invincible. Only a few Cassandras saw the turning in the road. The giddy rise in house prices skidded to a halt when the European Central Bank raised interest rates in 2006 and 2007. Construction sites closed abruptly and tens of thousands of workers were thrown out of work, many of them the immigrants on whom much of the future housing demand relied. Banks and developers on a giddy round of musical chairs were caught when the music stopped. Our crash was even “crashier” – to borrow Bertie’s unique word treatment – than any other country in Europe

The true value of half-completed housing developments on stunningly obscure sites in the so-called commuter counties lies savagely exposed. Agricultural land bought for astronomical sums at the height of the boom are reduced to wasteland. “Zombie” hotels, “ghost” estates and mothballed apartment blocks mock the hubris of another era, like the desert kingdom of Ozymandias : “Look on my works, ye Mighty, and dispair!”.

For 10 years, Ireland’s boom just got “boomier”, in the words of former Taoiseach, Bertie Ahern. From 1996, house prices rose without a break, pumped with the most potent drug of all : cheap credit and plenty of it. Flimsy financial regulation, tax incentives and soaring numbers of economic immigrants - many of them put to work on construction, thereby creating a vicious circle – ensured that property became the dinner party staple of the era.

An unholy alliance of builders, developers, estate agents and bankers became the new gentry, mad with hubris, prospering in a culture of greed masquerading as entrepreneurship. Their conspicuous lifestyles - trophy homes, multiple holiday villas, yachts, helicopters and the occasional private jet - were not only accepted, but admired as the well-earned fruits of their buccaneering labours.

At government and local level, politicians facilitated the developers, riding roughshod over planning principles and re-zoning parcels of agricultural land in areas unfit for development. Landowners became multimillionaires overnight, as the builders moved in to throw up insanely over-priced suburban-style houses in rural locations, all of it . financed by bankers driven by rivalry and minimal oversight.

Developers never had to worry about turning a profit, thanks to extraordinary house inflation, fast becoming a bubble. As desperate young couples were forced further from the city for affordable homes and overnight queues became a common feature of new home launches, agents and developers found new ways to milk the frenzy. Where before, phases one and two of a development might be a year apart, the greed fest reached a pitch where an apartment advertised at 270,000 on a Thursday morning could be hiked to 295,000 in a so-called “Phase 2” that same afternoon. Between 2000 and 2007, residential mortgage lending surged by more than 300 per cent - from 29 billion to 123 billion.

The disease was contagious. In the 10 years from 1996, as the Dublin region saw a 366% rise in property values – from an average of €82,400 to €384,247 - many with modest homes in the most non-descript suburb came to believe they were sitting on a goldmine and borrowed gleefully on the strength of it. Some came to fancy themselves as property “experts”. An age of insanity was distilled in one court case in early 2009, where it emerged that a Dublin father of three on an Air Corps pilot’s salary of 53,000 (euro), had managed to build up a twelve-house property portfolio, with loans of 8million euro from nine separate financial institutions.

The common belief, it seemed, was that cheap credit and immigration would last forever. We were invincible. Only a few Cassandras saw the turning in the road. The giddy rise in house prices skidded to a halt when the European Central Bank raised interest rates in 2006 and 2007. Construction sites closed abruptly and tens of thousands of workers were thrown out of work, many of them the immigrants on whom much of the future housing demand relied. Banks and developers on a giddy round of musical chairs were caught when the music stopped. Our crash was even “crashier” – to borrow Bertie’s unique word treatment – than any other country in Europe

The true value of half-completed housing developments on stunningly obscure sites in the so-called commuter counties lies savagely exposed. Agricultural land bought for astronomical sums at the height of the boom are reduced to wasteland. “Zombie” hotels, “ghost” estates and mothballed apartment blocks mock the hubris of another era, like the desert kingdom of Ozymandias : “Look on my works, ye Mighty, and dispair!”.

For 10 years, Ireland’s boom just got “boomier”, in the words of former Taoiseach, Bertie Ahern. From 1996, house prices rose without a break, pumped with the most potent drug of all : cheap credit and plenty of it. Flimsy financial regulation, tax incentives and soaring numbers of economic immigrants - many of them put to work on construction, thereby creating a vicious circle – ensured that property became the dinner party staple of the era.

An unholy alliance of builders, developers, estate agents and bankers became the new gentry, mad with hubris, prospering in a culture of greed masquerading as entrepreneurship. Their conspicuous lifestyles - trophy homes, multiple holiday villas, yachts, helicopters and the occasional private jet - were not only accepted, but admired as the well-earned fruits of their buccaneering labours.

At government and local level, politicians facilitated the developers, riding roughshod over planning principles and re-zoning parcels of agricultural land in areas unfit for development. Landowners became multimillionaires overnight, as the builders moved in to throw up insanely over-priced suburban-style houses in rural locations, all of it . financed by bankers driven by rivalry and minimal oversight.

Developers never had to worry about turning a profit, thanks to extraordinary house inflation, fast becoming a bubble. As desperate young couples were forced further from the city for affordable homes and overnight queues became a common feature of new home launches, agents and developers found new ways to milk the frenzy. Where before, phases one and two of a development might be a year apart, the greed fest reached a pitch where an apartment advertised at 270,000 on a Thursday morning could be hiked to 295,000 in a so-called “Phase 2” that same afternoon. Between 2000 and 2007, residential mortgage lending surged by more than 300 per cent - from 29 billion to 123 billion.

The disease was contagious. In the 10 years from 1996, as the Dublin region saw a 366% rise in property values – from an average of €82,400 to €384,247 - many with modest homes in the most non-descript suburb came to believe they were sitting on a goldmine and borrowed gleefully on the strength of it. Some came to fancy themselves as property “experts”. An age of insanity was distilled in one court case in early 2009, where it emerged that a Dublin father of three on an Air Corps pilot’s salary of 53,000 (euro), had managed to build up a twelve-house property portfolio, with loans of 8million euro from nine separate financial institutions.

The common belief, it seemed, was that cheap credit and immigration would last forever. We were invincible. Only a few Cassandras saw the turning in the road. The giddy rise in house prices skidded to a halt when the European Central Bank raised interest rates in 2006 and 2007. Construction sites closed abruptly and tens of thousands of workers were thrown out of work, many of them the immigrants on whom much of the future housing demand relied. Banks and developers on a giddy round of musical chairs were caught when the music stopped. Our crash was even “crashier” – to borrow Bertie’s unique word treatment – than any other country in Europe

The true value of half-completed housing developments on stunningly obscure sites in the so-called commuter counties lies savagely exposed. Agricultural land bought for astronomical sums at the height of the boom are reduced to wasteland. “Zombie” hotels, “ghost” estates and mothballed apartment blocks mock the hubris of another era, like the desert kingdom of Ozymandias : “Look on my works, ye Mighty, and dispair!”.

For 10 years, Ireland’s boom just got “boomier”, in the words of former Taoiseach, Bertie Ahern. From 1996, house prices rose without a break, pumped with the most potent drug of all : cheap credit and plenty of it. Flimsy financial regulation, tax incentives and soaring numbers of economic immigrants - many of them put to work on construction, thereby creating a vicious circle – ensured that property became the dinner party staple of the era.

An unholy alliance of builders, developers, estate agents and bankers became the new gentry, mad with hubris, prospering in a culture of greed masquerading as entrepreneurship. Their conspicuous lifestyles - trophy homes, multiple holiday villas, yachts, helicopters and the occasional private jet - were not only accepted, but admired as the well-earned fruits of their buccaneering labours.

At government and local level, politicians facilitated the developers, riding roughshod over planning principles and re-zoning parcels of agricultural land in areas unfit for development. Landowners became multimillionaires overnight, as the builders moved in to throw up insanely over-priced suburban-style houses in rural locations, all of it . financed by bankers driven by rivalry and minimal oversight.

Developers never had to worry about turning a profit, thanks to extraordinary house inflation, fast becoming a bubble. As desperate young couples were forced further from the city for affordable homes and overnight queues became a common feature of new home launches, agents and developers found new ways to milk the frenzy. Where before, phases one and two of a development might be a year apart, the greed fest reached a pitch where an apartment advertised at 270,000 on a Thursday morning could be hiked to 295,000 in a so-called “Phase 2” that same afternoon. Between 2000 and 2007, residential mortgage lending surged by more than 300 per cent - from 29 billion to 123 billion.

The disease was contagious. In the 10 years from 1996, as the Dublin region saw a 366% rise in property values – from an average of €82,400 to €384,247 - many with modest homes in the most non-descript suburb came to believe they were sitting on a goldmine and borrowed gleefully on the strength of it. Some came to fancy themselves as property “experts”. An age of insanity was distilled in one court case in early 2009, where it emerged that a Dublin father of three on an Air Corps pilot’s salary of 53,000 (euro), had managed to build up a twelve-house property portfolio, with loans of 8million euro from nine separate financial institutions.

The common belief, it seemed, was that cheap credit and immigration would last forever. We were invincible. Only a few Cassandras saw the turning in the road. The giddy rise in house prices skidded to a halt when the European Central Bank raised interest rates in 2006 and 2007. Construction sites closed abruptly and tens of thousands of workers were thrown out of work, many of them the immigrants on whom much of the future housing demand relied. Banks and developers on a giddy round of musical chairs were caught when the music stopped. Our crash was even “crashier” – to borrow Bertie’s unique word treatment – than any other country in Europe

The true value of half-completed housing developments on stunningly obscure sites in the so-called commuter counties lies savagely exposed. Agricultural land bought for astronomical sums at the height of the boom are reduced to wasteland. “Zombie” hotels, “ghost” estates and mothballed apartment blocks mock the hubris of another era, like the desert kingdom of Ozymandias : “Look on my works, ye Mighty, and dispair!”.

For 10 years, Ireland’s boom just got “boomier”, in the words of former Taoiseach, Bertie Ahern. From 1996, house prices rose without a break, pumped with the most potent drug of all : cheap credit and plenty of it. Flimsy financial regulation, tax incentives and soaring numbers of economic immigrants - many of them put to work on construction, thereby creating a vicious circle – ensured that property became the dinner party staple of the era.

An unholy alliance of builders, developers, estate agents and bankers became the new gentry, mad with hubris, prospering in a culture of greed masquerading as entrepreneurship. Their conspicuous lifestyles - trophy homes, multiple holiday villas, yachts, helicopters and the occasional private jet - were not only accepted, but admired as the well-earned fruits of their buccaneering labours.

At government and local level, politicians facilitated the developers, riding roughshod over planning principles and re-zoning parcels of agricultural land in areas unfit for development. Landowners became multimillionaires overnight, as the builders moved in to throw up insanely over-priced suburban-style houses in rural locations, all of it . financed by bankers driven by rivalry and minimal oversight.

Developers never had to worry about turning a profit, thanks to extraordinary house inflation, fast becoming a bubble. As desperate young couples were forced further from the city for affordable homes and overnight queues became a common feature of new home launches, agents and developers found new ways to milk the frenzy. Where before, phases one and two of a development might be a year apart, the greed fest reached a pitch where an apartment advertised at 270,000 on a Thursday morning could be hiked to 295,000 in a so-called “Phase 2” that same afternoon. Between 2000 and 2007, residential mortgage lending surged by more than 300 per cent - from 29 billion to 123 billion.

The disease was contagious. In the 10 years from 1996, as the Dublin region saw a 366% rise in property values – from an average of €82,400 to €384,247 - many with modest homes in the most non-descript suburb came to believe they were sitting on a goldmine and borrowed gleefully on the strength of it. Some came to fancy themselves as property “experts”. An age of insanity was distilled in one court case in early 2009, where it emerged that a Dublin father of three on an Air Corps pilot’s salary of 53,000 (euro), had managed to build up a twelve-house property portfolio, with loans of 8million euro from nine separate financial institutions.

The common belief, it seemed, was that cheap credit and immigration would last forever. We were invincible. Only a few Cassandras saw the turning in the road. The giddy rise in house prices skidded to a halt when the European Central Bank raised interest rates in 2006 and 2007. Construction sites closed abruptly and tens of thousands of workers were thrown out of work, many of them the immigrants on whom much of the future housing demand relied. Banks and developers on a giddy round of musical chairs were caught when the music stopped. Our crash was even “crashier” – to borrow Bertie’s unique word treatment – than any other country in Europe

The true value of half-completed housing developments on stunningly obscure sites in the so-called commuter counties lies savagely exposed. Agricultural land bought for astronomical sums at the height of the boom are reduced to wasteland. “Zombie” hotels, “ghost” estates and mothballed apartment blocks mock the hubris of another era, like the desert kingdom of Ozymandias : “Look on my works, ye Mighty, and dispair!”.

For 10 years, Ireland’s boom just got “boomier”, in the words of former Taoiseach, Bertie Ahern. From 1996, house prices rose without a break, pumped with the most potent drug of all : cheap credit and plenty of it. Flimsy financial regulation, tax incentives and soaring numbers of economic immigrants - many of them put to work on construction, thereby creating a vicious circle – ensured that property became the dinner party staple of the era.

An unholy alliance of builders, developers, estate agents and bankers became the new gentry, mad with hubris, prospering in a culture of greed masquerading as entrepreneurship. Their conspicuous lifestyles - trophy homes, multiple holiday villas, yachts, helicopters and the occasional private jet - were not only accepted, but admired as the well-earned fruits of their buccaneering labours.

At government and local level, politicians facilitated the developers, riding roughshod over planning principles and re-zoning parcels of agricultural land in areas unfit for development. Landowners became multimillionaires overnight, as the builders moved in to throw up insanely over-priced suburban-style houses in rural locations, all of it . financed by bankers driven by rivalry and minimal oversight.

Developers never had to worry about turning a profit, thanks to extraordinary house inflation, fast becoming a bubble. As desperate young couples were forced further from the city for affordable homes and overnight queues became a common feature of new home launches, agents and developers found new ways to milk the frenzy. Where before, phases one and two of a development might be a year apart, the greed fest reached a pitch where an apartment advertised at 270,000 on a Thursday morning could be hiked to 295,000 in a so-called “Phase 2” that same afternoon. Between 2000 and 2007, residential mortgage lending surged by more than 300 per cent - from 29 billion to 123 billion.

The disease was contagious. In the 10 years from 1996, as the Dublin region saw a 366% rise in property values – from an average of €82,400 to €384,247 - many with modest homes in the most non-descript suburb came to believe they were sitting on a goldmine and borrowed gleefully on the strength of it. Some came to fancy themselves as property “experts”. An age of insanity was distilled in one court case in early 2009, where it emerged that a Dublin father of three on an Air Corps pilot’s salary of 53,000 (euro), had managed to build up a twelve-house property portfolio, with loans of 8million euro from nine separate financial institutions.

The common belief, it seemed, was that cheap credit and immigration would last forever. We were invincible. Only a few Cassandras saw the turning in the road. The giddy rise in house prices skidded to a halt when the European Central Bank raised interest rates in 2006 and 2007. Construction sites closed abruptly and tens of thousands of workers were thrown out of work, many of them the immigrants on whom much of the future housing demand relied. Banks and developers on a giddy round of musical chairs were caught when the music stopped. Our crash was even “crashier” – to borrow Bertie’s unique word treatment – than any other country in Europe

The true value of half-completed housing developments on stunningly obscure sites in the so-called commuter counties lies savagely exposed. Agricultural land bought for astronomical sums at the height of the boom are reduced to wasteland. “Zombie” hotels, “ghost” estates and mothballed apartment blocks mock the hubris of another era, like the desert kingdom of Ozymandias : “Look on my works, ye Mighty, and dispair!”.

For 10 years, Ireland’s boom just got “boomier”, in the words of former Taoiseach, Bertie Ahern. From 1996, house prices rose without a break, pumped with the most potent drug of all : cheap credit and plenty of it. Flimsy financial regulation, tax incentives and soaring numbers of economic immigrants - many of them put to work on construction, thereby creating a vicious circle – ensured that property became the dinner party staple of the era.

An unholy alliance of builders, developers, estate agents and bankers became the new gentry, mad with hubris, prospering in a culture of greed masquerading as entrepreneurship. Their conspicuous lifestyles - trophy homes, multiple holiday villas, yachts, helicopters and the occasional private jet - were not only accepted, but admired as the well-earned fruits of their buccaneering labours.

At government and local level, politicians facilitated the developers, riding roughshod over planning principles and re-zoning parcels of agricultural land in areas unfit for development. Landowners became multimillionaires overnight, as the builders moved in to throw up insanely over-priced suburban-style houses in rural locations, all of it . financed by bankers driven by rivalry and minimal oversight.

Developers never had to worry about turning a profit, thanks to extraordinary house inflation, fast becoming a bubble. As desperate young couples were forced further from the city for affordable homes and overnight queues became a common feature of new home launches, agents and developers found new ways to milk the frenzy. Where before, phases one and two of a development might be a year apart, the greed fest reached a pitch where an apartment advertised at 270,000 on a Thursday morning could be hiked to 295,000 in a so-called “Phase 2” that same afternoon. Between 2000 and 2007, residential mortgage lending surged by more than 300 per cent - from 29 billion to 123 billion.

The disease was contagious. In the 10 years from 1996, as the Dublin region saw a 366% rise in property values – from an average of €82,400 to €384,247 - many with modest homes in the most non-descript suburb came to believe they were sitting on a goldmine and borrowed gleefully on the strength of it. Some came to fancy themselves as property “experts”. An age of insanity was distilled in one court case in early 2009, where it emerged that a Dublin father of three on an Air Corps pilot’s salary of 53,000 (euro), had managed to build up a twelve-house property portfolio, with loans of 8million euro from nine separate financial institutions.

The common belief, it seemed, was that cheap credit and immigration would last forever. We were invincible. Only a few Cassandras saw the turning in the road. The giddy rise in house prices skidded to a halt when the European Central Bank raised interest rates in 2006 and 2007. Construction sites closed abruptly and tens of thousands of workers were thrown out of work, many of them the immigrants on whom much of the future housing demand relied. Banks and developers on a giddy round of musical chairs were caught when the music stopped. Our crash was even “crashier” – to borrow Bertie’s unique word treatment – than any other country in Europe

The true value of half-completed housing developments on stunningly obscure sites in the so-called commuter counties lies savagely exposed. Agricultural land bought for astronomical sums at the height of the boom are reduced to wasteland. “Zombie” hotels, “ghost” estates and mothballed apartment blocks mock the hubris of another era, like the desert kingdom of Ozymandias : “Look on my works, ye Mighty, and dispair!”.

For 10 years, Ireland’s boom just got “boomier”, in the words of former Taoiseach, Bertie Ahern. From 1996, house prices rose without a break, pumped with the most potent drug of all : cheap credit and plenty of it. Flimsy financial regulation, tax incentives and soaring numbers of economic immigrants - many of them put to work on construction, thereby creating a vicious circle – ensured that property became the dinner party staple of the era.

An unholy alliance of builders, developers, estate agents and bankers became the new gentry, mad with hubris, prospering in a culture of greed masquerading as entrepreneurship. Their conspicuous lifestyles - trophy homes, multiple holiday villas, yachts, helicopters and the occasional private jet - were not only accepted, but admired as the well-earned fruits of their buccaneering labours.

At government and local level, politicians facilitated the developers, riding roughshod over planning principles and re-zoning parcels of agricultural land in areas unfit for development. Landowners became multimillionaires overnight, as the builders moved in to throw up insanely over-priced suburban-style houses in rural locations, all of it . financed by bankers driven by rivalry and minimal oversight.

Developers never had to worry about turning a profit, thanks to extraordinary house inflation, fast becoming a bubble. As desperate young couples were forced further from the city for affordable homes and overnight queues became a common feature of new home launches, agents and developers found new ways to milk the frenzy. Where before, phases one and two of a development might be a year apart, the greed fest reached a pitch where an apartment advertised at 270,000 on a Thursday morning could be hiked to 295,000 in a so-called “Phase 2” that same afternoon. Between 2000 and 2007, residential mortgage lending surged by more than 300 per cent - from 29 billion to 123 billion.

The disease was contagious. In the 10 years from 1996, as the Dublin region saw a 366% rise in property values – from an average of €82,400 to €384,247 - many with modest homes in the most non-descript suburb came to believe they were sitting on a goldmine and borrowed gleefully on the strength of it. Some came to fancy themselves as property “experts”. An age of insanity was distilled in one court case in early 2009, where it emerged that a Dublin father of three on an Air Corps pilot’s salary of 53,000 (euro), had managed to build up a twelve-house property portfolio, with loans of 8million euro from nine separate financial institutions.

The common belief, it seemed, was that cheap credit and immigration would last forever. We were invincible. Only a few Cassandras saw the turning in the road. The giddy rise in house prices skidded to a halt when the European Central Bank raised interest rates in 2006 and 2007. Construction sites closed abruptly and tens of thousands of workers were thrown out of work, many of them the immigrants on whom much of the future housing demand relied. Banks and developers on a giddy round of musical chairs were caught when the music stopped. Our crash was even “crashier” – to borrow Bertie’s unique word treatment – than any other country in Europe

The true value of half-completed housing developments on stunningly obscure sites in the so-called commuter counties lies savagely exposed. Agricultural land bought for astronomical sums at the height of the boom are reduced to wasteland. “Zombie” hotels, “ghost” estates and mothballed apartment blocks mock the hubris of another era, like the desert kingdom of Ozymandias : “Look on my works, ye Mighty, and dispair!”.

For 10 years, Ireland’s boom just got “boomier”, in the words of former Taoiseach, Bertie Ahern. From 1996, house prices rose without a break, pumped with the most potent drug of all : cheap credit and plenty of it. Flimsy financial regulation, tax incentives and soaring numbers of economic immigrants - many of them put to work on construction, thereby creating a vicious circle – ensured that property became the dinner party staple of the era.

An unholy alliance of builders, developers, estate agents and bankers became the new gentry, mad with hubris, prospering in a culture of greed masquerading as entrepreneurship. Their conspicuous lifestyles - trophy homes, multiple holiday villas, yachts, helicopters and the occasional private jet - were not only accepted, but admired as the well-earned fruits of their buccaneering labours.

At government and local level, politicians facilitated the developers, riding roughshod over planning principles and re-zoning parcels of agricultural land in areas unfit for development. Landowners became multimillionaires overnight, as the builders moved in to throw up insanely over-priced suburban-style houses in rural locations, all of it . financed by bankers driven by rivalry and minimal oversight.

Developers never had to worry about turning a profit, thanks to extraordinary house inflation, fast becoming a bubble. As desperate young couples were forced further from the city for affordable homes and overnight queues became a common feature of new home launches, agents and developers found new ways to milk the frenzy. Where before, phases one and two of a development might be a year apart, the greed fest reached a pitch where an apartment advertised at 270,000 on a Thursday morning could be hiked to 295,000 in a so-called “Phase 2” that same afternoon. Between 2000 and 2007, residential mortgage lending surged by more than 300 per cent - from 29 billion to 123 billion.

The disease was contagious. In the 10 years from 1996, as the Dublin region saw a 366% rise in property values – from an average of €82,400 to €384,247 - many with modest homes in the most non-descript suburb came to believe they were sitting on a goldmine and borrowed gleefully on the strength of it. Some came to fancy themselves as property “experts”. An age of insanity was distilled in one court case in early 2009, where it emerged that a Dublin father of three on an Air Corps pilot’s salary of 53,000 (euro), had managed to build up a twelve-house property portfolio, with loans of 8million euro from nine separate financial institutions.

The common belief, it seemed, was that cheap credit and immigration would last forever. We were invincible. Only a few Cassandras saw the turning in the road. The giddy rise in house prices skidded to a halt when the European Central Bank raised interest rates in 2006 and 2007. Construction sites closed abruptly and tens of thousands of workers were thrown out of work, many of them the immigrants on whom much of the future housing demand relied. Banks and developers on a giddy round of musical chairs were caught when the music stopped. Our crash was even “crashier” – to borrow Bertie’s unique word treatment – than any other country in Europe

The true value of half-completed housing developments on stunningly obscure sites in the so-called commuter counties lies savagely exposed. Agricultural land bought for astronomical sums at the height of the boom are reduced to wasteland. “Zombie” hotels, “ghost” estates and mothballed apartment blocks mock the hubris of another era, like the desert kingdom of Ozymandias : “Look on my works, ye Mighty, and dispair!”.

For 10 years, Ireland’s boom just got “boomier”, in the words of former Taoiseach, Bertie Ahern. From 1996, house prices rose without a break, pumped with the most potent drug of all : cheap credit and plenty of it. Flimsy financial regulation, tax incentives and soaring numbers of economic immigrants - many of them put to work on construction, thereby creating a vicious circle – ensured that property became the dinner party staple of the era.

An unholy alliance of builders, developers, estate agents and bankers became the new gentry, mad with hubris, prospering in a culture of greed masquerading as entrepreneurship. Their conspicuous lifestyles - trophy homes, multiple holiday villas, yachts, helicopters and the occasional private jet - were not only accepted, but admired as the well-earned fruits of their buccaneering labours.

At government and local level, politicians facilitated the developers, riding roughshod over planning principles and re-zoning parcels of agricultural land in areas unfit for development. Landowners became multimillionaires overnight, as the builders moved in to throw up insanely over-priced suburban-style houses in rural locations, all of it . financed by bankers driven by rivalry and minimal oversight.

Developers never had to worry about turning a profit, thanks to extraordinary house inflation, fast becoming a bubble. As desperate young couples were forced further from the city for affordable homes and overnight queues became a common feature of new home launches, agents and developers found new ways to milk the frenzy. Where before, phases one and two of a development might be a year apart, the greed fest reached a pitch where an apartment advertised at 270,000 on a Thursday morning could be hiked to 295,000 in a so-called “Phase 2” that same afternoon. Between 2000 and 2007, residential mortgage lending surged by more than 300 per cent - from 29 billion to 123 billion.

The disease was contagious. In the 10 years from 1996, as the Dublin region saw a 366% rise in property values – from an average of €82,400 to €384,247 - many with modest homes in the most non-descript suburb came to believe they were sitting on a goldmine and borrowed gleefully on the strength of it. Some came to fancy themselves as property “experts”. An age of insanity was distilled in one court case in early 2009, where it emerged that a Dublin father of three on an Air Corps pilot’s salary of 53,000 (euro), had managed to build up a twelve-house property portfolio, with loans of 8million euro from nine separate financial institutions.

The common belief, it seemed, was that cheap credit and immigration would last forever. We were invincible. Only a few Cassandras saw the turning in the road. The giddy rise in house prices skidded to a halt when the European Central Bank raised interest rates in 2006 and 2007. Construction sites closed abruptly and tens of thousands of workers were thrown out of work, many of them the immigrants on whom much of the future housing demand relied. Banks and developers on a giddy round of musical chairs were caught when the music stopped. Our crash was even “crashier” – to borrow Bertie’s unique word treatment – than any other country in Europe

The true value of half-completed housing developments on stunningly obscure sites in the so-called commuter counties lies savagely exposed. Agricultural land bought for astronomical sums at the height of the boom are reduced to wasteland. “Zombie” hotels, “ghost” estates and mothballed apartment blocks mock the hubris of another era, like the desert kingdom of Ozymandias : “Look on my works, ye Mighty, and dispair!”.

For 10 years, Ireland’s boom just got “boomier”, in the words of former Taoiseach, Bertie Ahern. From 1996, house prices rose without a break, pumped with the most potent drug of all : cheap credit and plenty of it. Flimsy financial regulation, tax incentives and soaring numbers of economic immigrants - many of them put to work on construction, thereby creating a vicious circle – ensured that property became the dinner party staple of the era.

An unholy alliance of builders, developers, estate agents and bankers became the new gentry, mad with hubris, prospering in a culture of greed masquerading as entrepreneurship. Their conspicuous lifestyles - trophy homes, multiple holiday villas, yachts, helicopters and the occasional private jet - were not only accepted, but admired as the well-earned fruits of their buccaneering labours.

At government and local level, politicians facilitated the developers, riding roughshod over planning principles and re-zoning parcels of agricultural land in areas unfit for development. Landowners became multimillionaires overnight, as the builders moved in to throw up insanely over-priced suburban-style houses in rural locations, all of it . financed by bankers driven by rivalry and minimal oversight.

Developers never had to worry about turning a profit, thanks to extraordinary house inflation, fast becoming a bubble. As desperate young couples were forced further from the city for affordable homes and overnight queues became a common feature of new home launches, agents and developers found new ways to milk the frenzy. Where before, phases one and two of a development might be a year apart, the greed fest reached a pitch where an apartment advertised at 270,000 on a Thursday morning could be hiked to 295,000 in a so-called “Phase 2” that same afternoon. Between 2000 and 2007, residential mortgage lending surged by more than 300 per cent - from 29 billion to 123 billion.

The disease was contagious. In the 10 years from 1996, as the Dublin region saw a 366% rise in property values – from an average of €82,400 to €384,247 - many with modest homes in the most non-descript suburb came to believe they were sitting on a goldmine and borrowed gleefully on the strength of it. Some came to fancy themselves as property “experts”. An age of insanity was distilled in one court case in early 2009, where it emerged that a Dublin father of three on an Air Corps pilot’s salary of 53,000 (euro), had managed to build up a twelve-house property portfolio, with loans of 8million euro from nine separate financial institutions.

The common belief, it seemed, was that cheap credit and immigration would last forever. We were invincible. Only a few Cassandras saw the turning in the road. The giddy rise in house prices skidded to a halt when the European Central Bank raised interest rates in 2006 and 2007. Construction sites closed abruptly and tens of thousands of workers were thrown out of work, many of them the immigrants on whom much of the future housing demand relied. Banks and developers on a giddy round of musical chairs were caught when the music stopped. Our crash was even “crashier” – to borrow Bertie’s unique word treatment – than any other country in Europe

The true value of half-completed housing developments on stunningly obscure sites in the so-called commuter counties lies savagely exposed. Agricultural land bought for astronomical sums at the height of the boom are reduced to wasteland. “Zombie” hotels, “ghost” estates and mothballed apartment blocks mock the hubris of another era, like the desert kingdom of Ozymandias : “Look on my works, ye Mighty, and dispair!”.

For 10 years, Ireland’s boom just got “boomier”, in the words of former Taoiseach, Bertie Ahern. From 1996, house prices rose without a break, pumped with the most potent drug of all : cheap credit and plenty of it. Flimsy financial regulation, tax incentives and soaring numbers of economic immigrants - many of them put to work on construction, thereby creating a vicious circle – ensured that property became the dinner party staple of the era.

An unholy alliance of builders, developers, estate agents and bankers became the new gentry, mad with hubris, prospering in a culture of greed masquerading as entrepreneurship. Their conspicuous lifestyles - trophy homes, multiple holiday villas, yachts, helicopters and the occasional private jet - were not only accepted, but admired as the well-earned fruits of their buccaneering labours.

At government and local level, politicians facilitated the developers, riding roughshod over planning principles and re-zoning parcels of agricultural land in areas unfit for development. Landowners became multimillionaires overnight, as the builders moved in to throw up insanely over-priced suburban-style houses in rural locations, all of it . financed by bankers driven by rivalry and minimal oversight.

Developers never had to worry about turning a profit, thanks to extraordinary house inflation, fast becoming a bubble. As desperate young couples were forced further from the city for affordable homes and overnight queues became a common feature of new home launches, agents and developers found new ways to milk the frenzy. Where before, phases one and two of a development might be a year apart, the greed fest reached a pitch where an apartment advertised at 270,000 on a Thursday morning could be hiked to 295,000 in a so-called “Phase 2” that same afternoon. Between 2000 and 2007, residential mortgage lending surged by more than 300 per cent - from 29 billion to 123 billion.

The disease was contagious. In the 10 years from 1996, as the Dublin region saw a 366% rise in property values – from an average of €82,400 to €384,247 - many with modest homes in the most non-descript suburb came to believe they were sitting on a goldmine and borrowed gleefully on the strength of it. Some came to fancy themselves as property “experts”. An age of insanity was distilled in one court case in early 2009, where it emerged that a Dublin father of three on an Air Corps pilot’s salary of 53,000 (euro), had managed to build up a twelve-house property portfolio, with loans of 8million euro from nine separate financial institutions.

The common belief, it seemed, was that cheap credit and immigration would last forever. We were invincible. Only a few Cassandras saw the turning in the road. The giddy rise in house prices skidded to a halt when the European Central Bank raised interest rates in 2006 and 2007. Construction sites closed abruptly and tens of thousands of workers were thrown out of work, many of them the immigrants on whom much of the future housing demand relied. Banks and developers on a giddy round of musical chairs were caught when the music stopped. Our crash was even “crashier” – to borrow Bertie’s unique word treatment – than any other country in Europe

The true value of half-completed housing developments on stunningly obscure sites in the so-called commuter counties lies savagely exposed. Agricultural land bought for astronomical sums at the height of the boom are reduced to wasteland. “Zombie” hotels, “ghost” estates and mothballed apartment blocks mock the hubris of another era, like the desert kingdom of Ozymandias : “Look on my works, ye Mighty, and dispair!”.

For 10 years, Ireland’s boom just got “boomier”, in the words of former Taoiseach, Bertie Ahern. From 1996, house prices rose without a break, pumped with the most potent drug of all : cheap credit and plenty of it. Flimsy financial regulation, tax incentives and soaring numbers of economic immigrants - many of them put to work on construction, thereby creating a vicious circle – ensured that property became the dinner party staple of the era.

An unholy alliance of builders, developers, estate agents and bankers became the new gentry, mad with hubris, prospering in a culture of greed masquerading as entrepreneurship. Their conspicuous lifestyles - trophy homes, multiple holiday villas, yachts, helicopters and the occasional private jet - were not only accepted, but admired as the well-earned fruits of their buccaneering labours.

At government and local level, politicians facilitated the developers, riding roughshod over planning principles and re-zoning parcels of agricultural land in areas unfit for development. Landowners became multimillionaires overnight, as the builders moved in to throw up insanely over-priced suburban-style houses in rural locations, all of it . financed by bankers driven by rivalry and minimal oversight.

Developers never had to worry about turning a profit, thanks to extraordinary house inflation, fast becoming a bubble. As desperate young couples were forced further from the city for affordable homes and overnight queues became a common feature of new home launches, agents and developers found new ways to milk the frenzy. Where before, phases one and two of a development might be a year apart, the greed fest reached a pitch where an apartment advertised at 270,000 on a Thursday morning could be hiked to 295,000 in a so-called “Phase 2” that same afternoon. Between 2000 and 2007, residential mortgage lending surged by more than 300 per cent - from 29 billion to 123 billion.

The disease was contagious. In the 10 years from 1996, as the Dublin region saw a 366% rise in property values – from an average of €82,400 to €384,247 - many with modest homes in the most non-descript suburb came to believe they were sitting on a goldmine and borrowed gleefully on the strength of it. Some came to fancy themselves as property “experts”. An age of insanity was distilled in one court case in early 2009, where it emerged that a Dublin father of three on an Air Corps pilot’s salary of 53,000 (euro), had managed to build up a twelve-house property portfolio, with loans of 8million euro from nine separate financial institutions.

The common belief, it seemed, was that cheap credit and immigration would last forever. We were invincible. Only a few Cassandras saw the turning in the road. The giddy rise in house prices skidded to a halt when the European Central Bank raised interest rates in 2006 and 2007. Construction sites closed abruptly and tens of thousands of workers were thrown out of work, many of them the immigrants on whom much of the future housing demand relied. Banks and developers on a giddy round of musical chairs were caught when the music stopped. Our crash was even “crashier” – to borrow Bertie’s unique word treatment – than any other country in Europe

The true value of half-completed housing developments on stunningly obscure sites in the so-called commuter counties lies savagely exposed. Agricultural land bought for astronomical sums at the height of the boom are reduced to wasteland. “Zombie” hotels, “ghost” estates and mothballed apartment blocks mock the hubris of another era, like the desert kingdom of Ozymandias : “Look on my works, ye Mighty, and dispair!”.

For 10 years, Ireland’s boom just got “boomier”, in the words of former Taoiseach, Bertie Ahern. From 1996, house prices rose without a break, pumped with the most potent drug of all : cheap credit and plenty of it. Flimsy financial regulation, tax incentives and soaring numbers of economic immigrants - many of them put to work on construction, thereby creating a vicious circle – ensured that property became the dinner party staple of the era.

An unholy alliance of builders, developers, estate agents and bankers became the new gentry, mad with hubris, prospering in a culture of greed masquerading as entrepreneurship. Their conspicuous lifestyles - trophy homes, multiple holiday villas, yachts, helicopters and the occasional private jet - were not only accepted, but admired as the well-earned fruits of their buccaneering labours.

At government and local level, politicians facilitated the developers, riding roughshod over planning principles and re-zoning parcels of agricultural land in areas unfit for development. Landowners became multimillionaires overnight, as the builders moved in to throw up insanely over-priced suburban-style houses in rural locations, all of it . financed by bankers driven by rivalry and minimal oversight.

Developers never had to worry about turning a profit, thanks to extraordinary house inflation, fast becoming a bubble. As desperate young couples were forced further from the city for affordable homes and overnight queues became a common feature of new home launches, agents and developers found new ways to milk the frenzy. Where before, phases one and two of a development might be a year apart, the greed fest reached a pitch where an apartment advertised at 270,000 on a Thursday morning could be hiked to 295,000 in a so-called “Phase 2” that same afternoon. Between 2000 and 2007, residential mortgage lending surged by more than 300 per cent - from 29 billion to 123 billion.

The disease was contagious. In the 10 years from 1996, as the Dublin region saw a 366% rise in property values – from an average of €82,400 to €384,247 - many with modest homes in the most non-descript suburb came to believe they were sitting on a goldmine and borrowed gleefully on the strength of it. Some came to fancy themselves as property “experts”. An age of insanity was distilled in one court case in early 2009, where it emerged that a Dublin father of three on an Air Corps pilot’s salary of 53,000 (euro), had managed to build up a twelve-house property portfolio, with loans of 8million euro from nine separate financial institutions.

The common belief, it seemed, was that cheap credit and immigration would last forever. We were invincible. Only a few Cassandras saw the turning in the road. The giddy rise in house prices skidded to a halt when the European Central Bank raised interest rates in 2006 and 2007. Construction sites closed abruptly and tens of thousands of workers were thrown out of work, many of them the immigrants on whom much of the future housing demand relied. Banks and developers on a giddy round of musical chairs were caught when the music stopped. Our crash was even “crashier” – to borrow Bertie’s unique word treatment – than any other country in Europe

The true value of half-completed housing developments on stunningly obscure sites in the so-called commuter counties lies savagely exposed. Agricultural land bought for astronomical sums at the height of the boom are reduced to wasteland. “Zombie” hotels, “ghost” estates and mothballed apartment blocks mock the hubris of another era, like the desert kingdom of Ozymandias : “Look on my works, ye Mighty, and dispair!”.

For 10 years, Ireland’s boom just got “boomier”, in the words of former Taoiseach, Bertie Ahern. From 1996, house prices rose without a break, pumped with the most potent drug of all : cheap credit and plenty of it. Flimsy financial regulation, tax incentives and soaring numbers of economic immigrants - many of them put to work on construction, thereby creating a vicious circle – ensured that property became the dinner party staple of the era.

An unholy alliance of builders, developers, estate agents and bankers became the new gentry, mad with hubris, prospering in a culture of greed masquerading as entrepreneurship. Their conspicuous lifestyles - trophy homes, multiple holiday villas, yachts, helicopters and the occasional private jet - were not only accepted, but admired as the well-earned fruits of their buccaneering labours.

At government and local level, politicians facilitated the developers, riding roughshod over planning principles and re-zoning parcels of agricultural land in areas unfit for development. Landowners became multimillionaires overnight, as the builders moved in to throw up insanely over-priced suburban-style houses in rural locations, all of it . financed by bankers driven by rivalry and minimal oversight.

Developers never had to worry about turning a profit, thanks to extraordinary house inflation, fast becoming a bubble. As desperate young couples were forced further from the city for affordable homes and overnight queues became a common feature of new home launches, agents and developers found new ways to milk the frenzy. Where before, phases one and two of a development might be a year apart, the greed fest reached a pitch where an apartment advertised at 270,000 on a Thursday morning could be hiked to 295,000 in a so-called “Phase 2” that same afternoon. Between 2000 and 2007, residential mortgage lending surged by more than 300 per cent - from 29 billion to 123 billion.