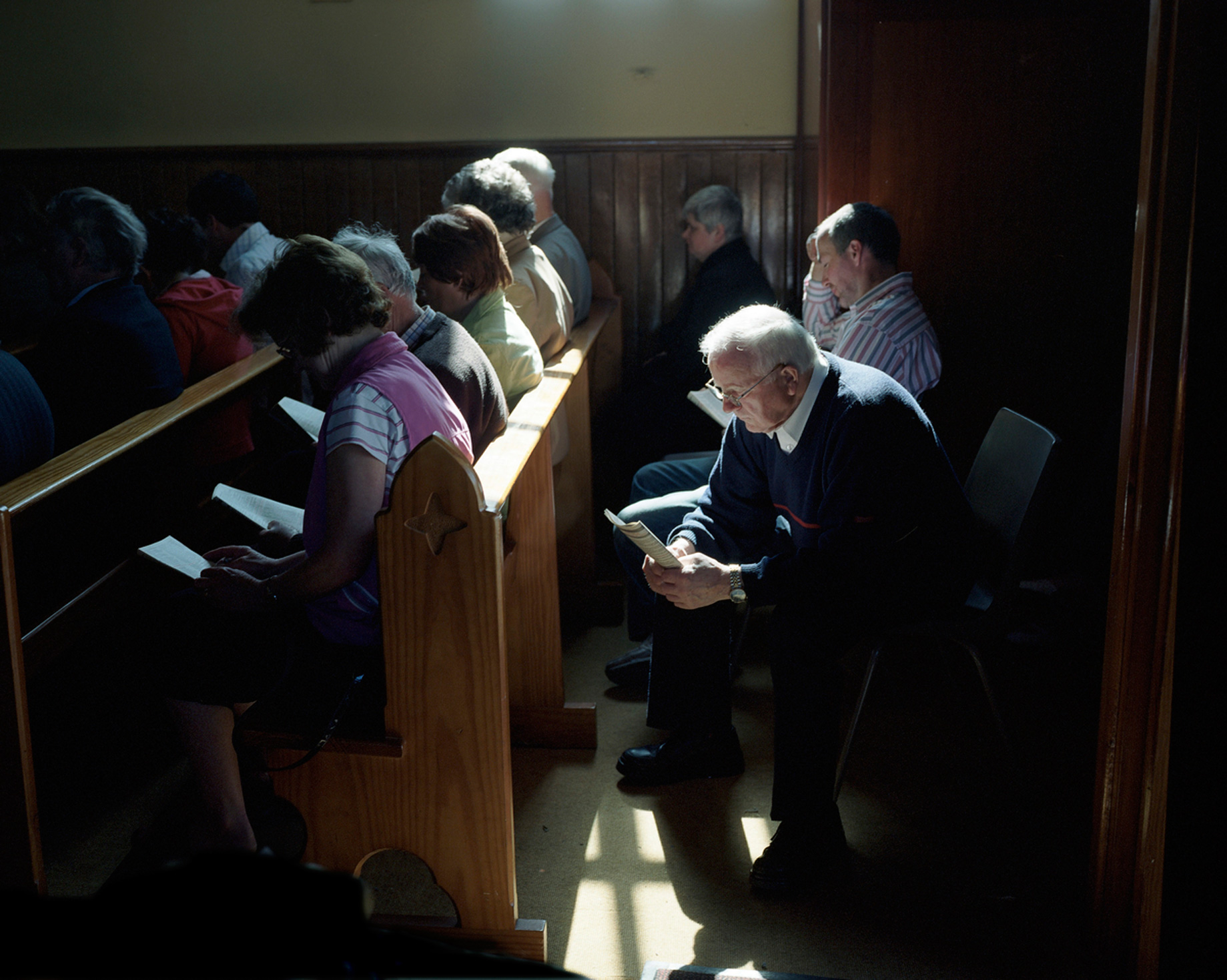

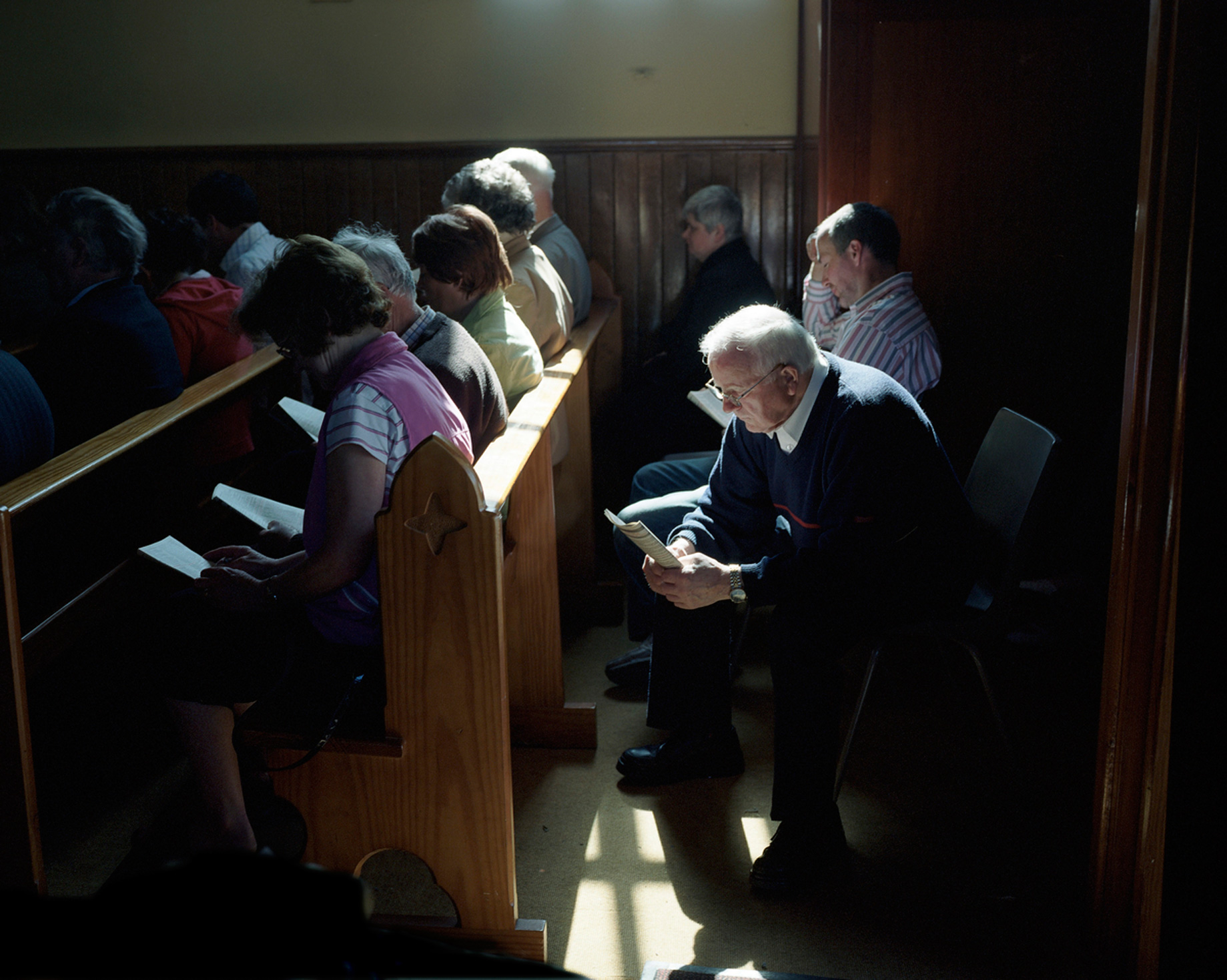

Though now a more secular society, Ireland still has remnants and relics of the old religious faith, even if many of its devoted followers are typically advanced in age – part of what might be termed a dying generation. The Catholic Church had been one of the country’s mainstays. Falling Mass attendances, declining priest numbers and various damaging scandals have shaken the institution and weakened its grip. Despite this my father is a daily Mass-goer; his faith doesn’t appear to have flinched.

The house where I grew up in the west of Ireland is where my father now resides with his wife and their daughter Susan; all the rest of the family have flown the nest, some starting families of their own, one in New York where she has become part of the Irish Diaspora. The religious paraphernalia located throughout this house gives God a central presence and status not uncommon in Ireland at the time. We prayed as a family, like when the Angelus bells struck at noon and six in the evening. We knelt at night to say the Holy Rosary. Many of our rites of passage as children were rooted in Catholicism – our first communion, our confirmation, and so on.

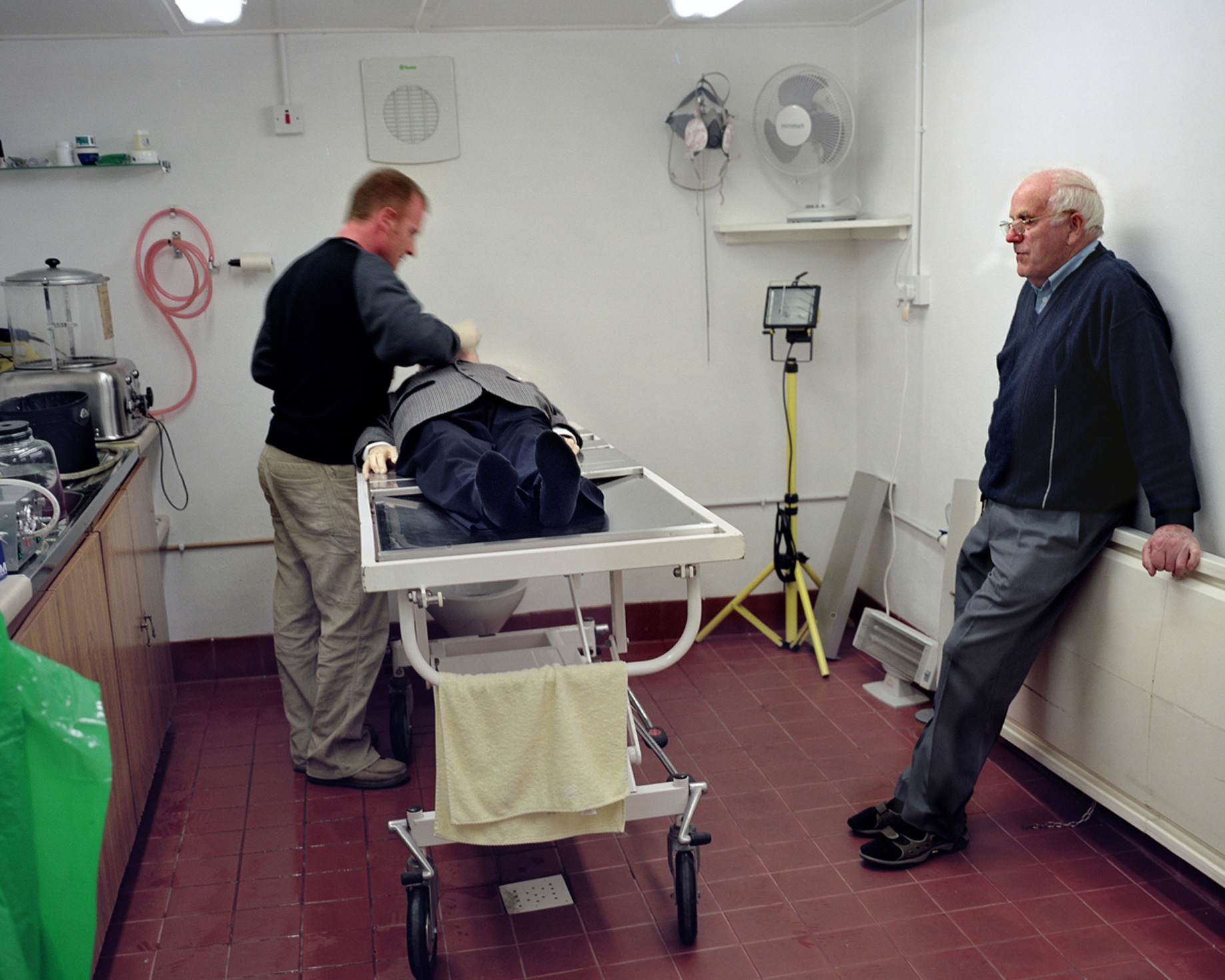

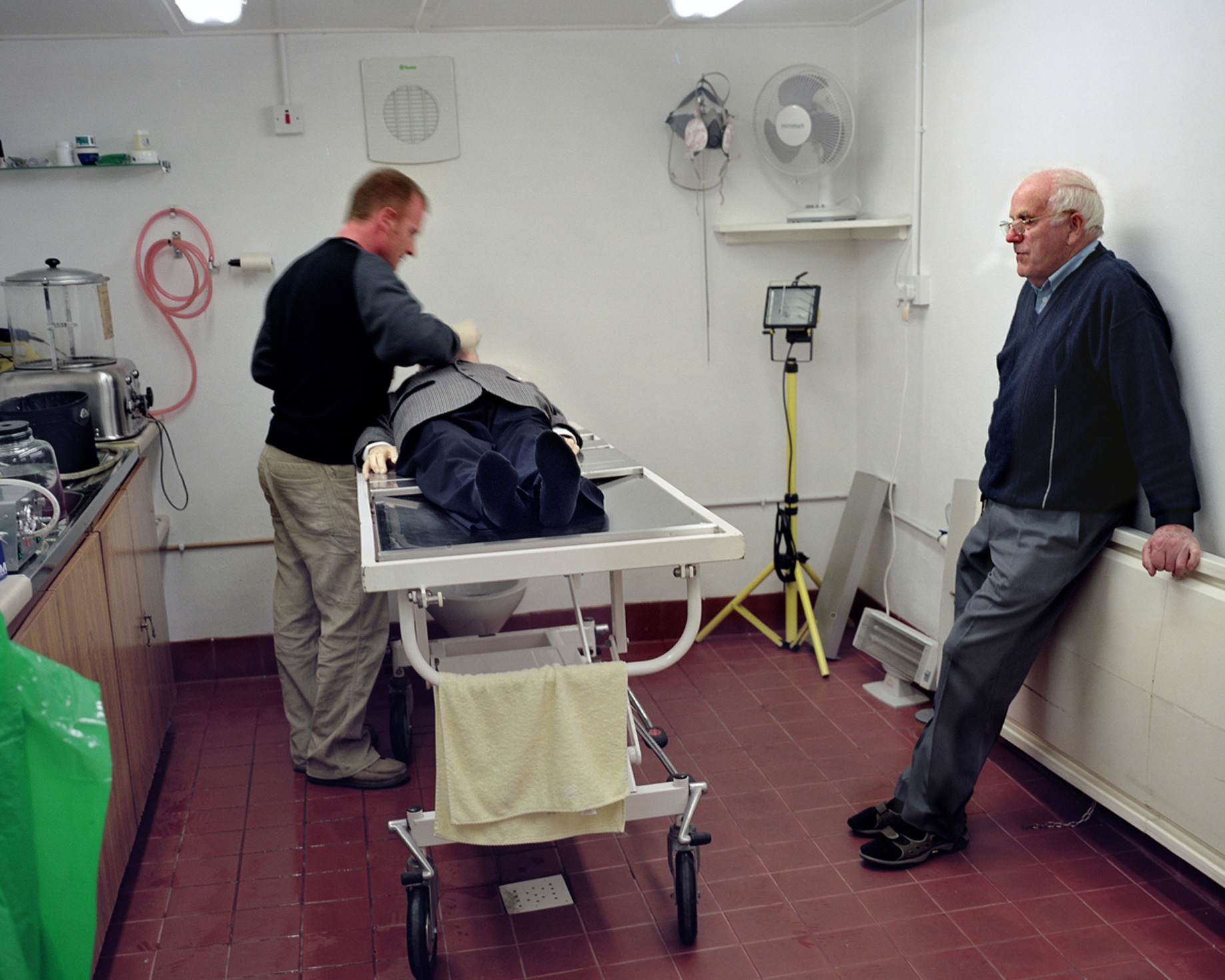

My father, who is 85, would not have seen anything remarkable in this. He was merely carrying on the tradition of his own father’s generation. Having spent half his life working, he recently retired, closing his drapery store. His undertaker’s business continues. For me and others in the family it meant that death was never far away or overtly mysterious. We became accustomed to the dead of our parish being prepared for the final ceremonies before burial. We would often come home from school to see who had died that day.

If we truly wanted to make our father proud, we would have mastered the game he followed all his life: hurling. This ancient Irish sport, requiring great dexterity, courage and speed, can still weave a spell on him. Born in a rural community he has seen his own life change and now that of his children too. In recent years he lost a brother to whom he was close. Now I see him deriving great joy from his grandchildren. In their company he seems tranquil. At peace. His work done.

Though now a more secular society, Ireland still has remnants and relics of the old religious faith, even if many of its devoted followers are typically advanced in age – part of what might be termed a dying generation. The Catholic Church had been one of the country’s mainstays. Falling Mass attendances, declining priest numbers and various damaging scandals have shaken the institution and weakened its grip. Despite this my father is a daily Mass-goer; his faith doesn’t appear to have flinched.

The house where I grew up in the west of Ireland is where my father now resides with his wife and their daughter Susan; all the rest of the family have flown the nest, some starting families of their own, one in New York where she has become part of the Irish Diaspora. The religious paraphernalia located throughout this house gives God a central presence and status not uncommon in Ireland at the time. We prayed as a family, like when the Angelus bells struck at noon and six in the evening. We knelt at night to say the Holy Rosary. Many of our rites of passage as children were rooted in Catholicism – our first communion, our confirmation, and so on.

My father, who is 85, would not have seen anything remarkable in this. He was merely carrying on the tradition of his own father’s generation. Having spent half his life working, he recently retired, closing his drapery store. His undertaker’s business continues. For me and others in the family it meant that death was never far away or overtly mysterious. We became accustomed to the dead of our parish being prepared for the final ceremonies before burial. We would often come home from school to see who had died that day.

If we truly wanted to make our father proud, we would have mastered the game he followed all his life: hurling. This ancient Irish sport, requiring great dexterity, courage and speed, can still weave a spell on him. Born in a rural community he has seen his own life change and now that of his children too. In recent years he lost a brother to whom he was close. Now I see him deriving great joy from his grandchildren. In their company he seems tranquil. At peace. His work done.

Though now a more secular society, Ireland still has remnants and relics of the old religious faith, even if many of its devoted followers are typically advanced in age – part of what might be termed a dying generation. The Catholic Church had been one of the country’s mainstays. Falling Mass attendances, declining priest numbers and various damaging scandals have shaken the institution and weakened its grip. Despite this my father is a daily Mass-goer; his faith doesn’t appear to have flinched.

The house where I grew up in the west of Ireland is where my father now resides with his wife and their daughter Susan; all the rest of the family have flown the nest, some starting families of their own, one in New York where she has become part of the Irish Diaspora. The religious paraphernalia located throughout this house gives God a central presence and status not uncommon in Ireland at the time. We prayed as a family, like when the Angelus bells struck at noon and six in the evening. We knelt at night to say the Holy Rosary. Many of our rites of passage as children were rooted in Catholicism – our first communion, our confirmation, and so on.

My father, who is 85, would not have seen anything remarkable in this. He was merely carrying on the tradition of his own father’s generation. Having spent half his life working, he recently retired, closing his drapery store. His undertaker’s business continues. For me and others in the family it meant that death was never far away or overtly mysterious. We became accustomed to the dead of our parish being prepared for the final ceremonies before burial. We would often come home from school to see who had died that day.

If we truly wanted to make our father proud, we would have mastered the game he followed all his life: hurling. This ancient Irish sport, requiring great dexterity, courage and speed, can still weave a spell on him. Born in a rural community he has seen his own life change and now that of his children too. In recent years he lost a brother to whom he was close. Now I see him deriving great joy from his grandchildren. In their company he seems tranquil. At peace. His work done.

Though now a more secular society, Ireland still has remnants and relics of the old religious faith, even if many of its devoted followers are typically advanced in age – part of what might be termed a dying generation. The Catholic Church had been one of the country’s mainstays. Falling Mass attendances, declining priest numbers and various damaging scandals have shaken the institution and weakened its grip. Despite this my father is a daily Mass-goer; his faith doesn’t appear to have flinched.

The house where I grew up in the west of Ireland is where my father now resides with his wife and their daughter Susan; all the rest of the family have flown the nest, some starting families of their own, one in New York where she has become part of the Irish Diaspora. The religious paraphernalia located throughout this house gives God a central presence and status not uncommon in Ireland at the time. We prayed as a family, like when the Angelus bells struck at noon and six in the evening. We knelt at night to say the Holy Rosary. Many of our rites of passage as children were rooted in Catholicism – our first communion, our confirmation, and so on.

My father, who is 85, would not have seen anything remarkable in this. He was merely carrying on the tradition of his own father’s generation. Having spent half his life working, he recently retired, closing his drapery store. His undertaker’s business continues. For me and others in the family it meant that death was never far away or overtly mysterious. We became accustomed to the dead of our parish being prepared for the final ceremonies before burial. We would often come home from school to see who had died that day.

If we truly wanted to make our father proud, we would have mastered the game he followed all his life: hurling. This ancient Irish sport, requiring great dexterity, courage and speed, can still weave a spell on him. Born in a rural community he has seen his own life change and now that of his children too. In recent years he lost a brother to whom he was close. Now I see him deriving great joy from his grandchildren. In their company he seems tranquil. At peace. His work done.

Though now a more secular society, Ireland still has remnants and relics of the old religious faith, even if many of its devoted followers are typically advanced in age – part of what might be termed a dying generation. The Catholic Church had been one of the country’s mainstays. Falling Mass attendances, declining priest numbers and various damaging scandals have shaken the institution and weakened its grip. Despite this my father is a daily Mass-goer; his faith doesn’t appear to have flinched.

The house where I grew up in the west of Ireland is where my father now resides with his wife and their daughter Susan; all the rest of the family have flown the nest, some starting families of their own, one in New York where she has become part of the Irish Diaspora. The religious paraphernalia located throughout this house gives God a central presence and status not uncommon in Ireland at the time. We prayed as a family, like when the Angelus bells struck at noon and six in the evening. We knelt at night to say the Holy Rosary. Many of our rites of passage as children were rooted in Catholicism – our first communion, our confirmation, and so on.

My father, who is 85, would not have seen anything remarkable in this. He was merely carrying on the tradition of his own father’s generation. Having spent half his life working, he recently retired, closing his drapery store. His undertaker’s business continues. For me and others in the family it meant that death was never far away or overtly mysterious. We became accustomed to the dead of our parish being prepared for the final ceremonies before burial. We would often come home from school to see who had died that day.

If we truly wanted to make our father proud, we would have mastered the game he followed all his life: hurling. This ancient Irish sport, requiring great dexterity, courage and speed, can still weave a spell on him. Born in a rural community he has seen his own life change and now that of his children too. In recent years he lost a brother to whom he was close. Now I see him deriving great joy from his grandchildren. In their company he seems tranquil. At peace. His work done.

Though now a more secular society, Ireland still has remnants and relics of the old religious faith, even if many of its devoted followers are typically advanced in age – part of what might be termed a dying generation. The Catholic Church had been one of the country’s mainstays. Falling Mass attendances, declining priest numbers and various damaging scandals have shaken the institution and weakened its grip. Despite this my father is a daily Mass-goer; his faith doesn’t appear to have flinched.

The house where I grew up in the west of Ireland is where my father now resides with his wife and their daughter Susan; all the rest of the family have flown the nest, some starting families of their own, one in New York where she has become part of the Irish Diaspora. The religious paraphernalia located throughout this house gives God a central presence and status not uncommon in Ireland at the time. We prayed as a family, like when the Angelus bells struck at noon and six in the evening. We knelt at night to say the Holy Rosary. Many of our rites of passage as children were rooted in Catholicism – our first communion, our confirmation, and so on.

My father, who is 85, would not have seen anything remarkable in this. He was merely carrying on the tradition of his own father’s generation. Having spent half his life working, he recently retired, closing his drapery store. His undertaker’s business continues. For me and others in the family it meant that death was never far away or overtly mysterious. We became accustomed to the dead of our parish being prepared for the final ceremonies before burial. We would often come home from school to see who had died that day.

If we truly wanted to make our father proud, we would have mastered the game he followed all his life: hurling. This ancient Irish sport, requiring great dexterity, courage and speed, can still weave a spell on him. Born in a rural community he has seen his own life change and now that of his children too. In recent years he lost a brother to whom he was close. Now I see him deriving great joy from his grandchildren. In their company he seems tranquil. At peace. His work done.

Though now a more secular society, Ireland still has remnants and relics of the old religious faith, even if many of its devoted followers are typically advanced in age – part of what might be termed a dying generation. The Catholic Church had been one of the country’s mainstays. Falling Mass attendances, declining priest numbers and various damaging scandals have shaken the institution and weakened its grip. Despite this my father is a daily Mass-goer; his faith doesn’t appear to have flinched.

The house where I grew up in the west of Ireland is where my father now resides with his wife and their daughter Susan; all the rest of the family have flown the nest, some starting families of their own, one in New York where she has become part of the Irish Diaspora. The religious paraphernalia located throughout this house gives God a central presence and status not uncommon in Ireland at the time. We prayed as a family, like when the Angelus bells struck at noon and six in the evening. We knelt at night to say the Holy Rosary. Many of our rites of passage as children were rooted in Catholicism – our first communion, our confirmation, and so on.

My father, who is 85, would not have seen anything remarkable in this. He was merely carrying on the tradition of his own father’s generation. Having spent half his life working, he recently retired, closing his drapery store. His undertaker’s business continues. For me and others in the family it meant that death was never far away or overtly mysterious. We became accustomed to the dead of our parish being prepared for the final ceremonies before burial. We would often come home from school to see who had died that day.

If we truly wanted to make our father proud, we would have mastered the game he followed all his life: hurling. This ancient Irish sport, requiring great dexterity, courage and speed, can still weave a spell on him. Born in a rural community he has seen his own life change and now that of his children too. In recent years he lost a brother to whom he was close. Now I see him deriving great joy from his grandchildren. In their company he seems tranquil. At peace. His work done.

Though now a more secular society, Ireland still has remnants and relics of the old religious faith, even if many of its devoted followers are typically advanced in age – part of what might be termed a dying generation. The Catholic Church had been one of the country’s mainstays. Falling Mass attendances, declining priest numbers and various damaging scandals have shaken the institution and weakened its grip. Despite this my father is a daily Mass-goer; his faith doesn’t appear to have flinched.

The house where I grew up in the west of Ireland is where my father now resides with his wife and their daughter Susan; all the rest of the family have flown the nest, some starting families of their own, one in New York where she has become part of the Irish Diaspora. The religious paraphernalia located throughout this house gives God a central presence and status not uncommon in Ireland at the time. We prayed as a family, like when the Angelus bells struck at noon and six in the evening. We knelt at night to say the Holy Rosary. Many of our rites of passage as children were rooted in Catholicism – our first communion, our confirmation, and so on.

My father, who is 85, would not have seen anything remarkable in this. He was merely carrying on the tradition of his own father’s generation. Having spent half his life working, he recently retired, closing his drapery store. His undertaker’s business continues. For me and others in the family it meant that death was never far away or overtly mysterious. We became accustomed to the dead of our parish being prepared for the final ceremonies before burial. We would often come home from school to see who had died that day.

If we truly wanted to make our father proud, we would have mastered the game he followed all his life: hurling. This ancient Irish sport, requiring great dexterity, courage and speed, can still weave a spell on him. Born in a rural community he has seen his own life change and now that of his children too. In recent years he lost a brother to whom he was close. Now I see him deriving great joy from his grandchildren. In their company he seems tranquil. At peace. His work done.

Though now a more secular society, Ireland still has remnants and relics of the old religious faith, even if many of its devoted followers are typically advanced in age – part of what might be termed a dying generation. The Catholic Church had been one of the country’s mainstays. Falling Mass attendances, declining priest numbers and various damaging scandals have shaken the institution and weakened its grip. Despite this my father is a daily Mass-goer; his faith doesn’t appear to have flinched.

The house where I grew up in the west of Ireland is where my father now resides with his wife and their daughter Susan; all the rest of the family have flown the nest, some starting families of their own, one in New York where she has become part of the Irish Diaspora. The religious paraphernalia located throughout this house gives God a central presence and status not uncommon in Ireland at the time. We prayed as a family, like when the Angelus bells struck at noon and six in the evening. We knelt at night to say the Holy Rosary. Many of our rites of passage as children were rooted in Catholicism – our first communion, our confirmation, and so on.

My father, who is 85, would not have seen anything remarkable in this. He was merely carrying on the tradition of his own father’s generation. Having spent half his life working, he recently retired, closing his drapery store. His undertaker’s business continues. For me and others in the family it meant that death was never far away or overtly mysterious. We became accustomed to the dead of our parish being prepared for the final ceremonies before burial. We would often come home from school to see who had died that day.

If we truly wanted to make our father proud, we would have mastered the game he followed all his life: hurling. This ancient Irish sport, requiring great dexterity, courage and speed, can still weave a spell on him. Born in a rural community he has seen his own life change and now that of his children too. In recent years he lost a brother to whom he was close. Now I see him deriving great joy from his grandchildren. In their company he seems tranquil. At peace. His work done.

Though now a more secular society, Ireland still has remnants and relics of the old religious faith, even if many of its devoted followers are typically advanced in age – part of what might be termed a dying generation. The Catholic Church had been one of the country’s mainstays. Falling Mass attendances, declining priest numbers and various damaging scandals have shaken the institution and weakened its grip. Despite this my father is a daily Mass-goer; his faith doesn’t appear to have flinched.

The house where I grew up in the west of Ireland is where my father now resides with his wife and their daughter Susan; all the rest of the family have flown the nest, some starting families of their own, one in New York where she has become part of the Irish Diaspora. The religious paraphernalia located throughout this house gives God a central presence and status not uncommon in Ireland at the time. We prayed as a family, like when the Angelus bells struck at noon and six in the evening. We knelt at night to say the Holy Rosary. Many of our rites of passage as children were rooted in Catholicism – our first communion, our confirmation, and so on.

My father, who is 85, would not have seen anything remarkable in this. He was merely carrying on the tradition of his own father’s generation. Having spent half his life working, he recently retired, closing his drapery store. His undertaker’s business continues. For me and others in the family it meant that death was never far away or overtly mysterious. We became accustomed to the dead of our parish being prepared for the final ceremonies before burial. We would often come home from school to see who had died that day.

If we truly wanted to make our father proud, we would have mastered the game he followed all his life: hurling. This ancient Irish sport, requiring great dexterity, courage and speed, can still weave a spell on him. Born in a rural community he has seen his own life change and now that of his children too. In recent years he lost a brother to whom he was close. Now I see him deriving great joy from his grandchildren. In their company he seems tranquil. At peace. His work done.

Though now a more secular society, Ireland still has remnants and relics of the old religious faith, even if many of its devoted followers are typically advanced in age – part of what might be termed a dying generation. The Catholic Church had been one of the country’s mainstays. Falling Mass attendances, declining priest numbers and various damaging scandals have shaken the institution and weakened its grip. Despite this my father is a daily Mass-goer; his faith doesn’t appear to have flinched.

The house where I grew up in the west of Ireland is where my father now resides with his wife and their daughter Susan; all the rest of the family have flown the nest, some starting families of their own, one in New York where she has become part of the Irish Diaspora. The religious paraphernalia located throughout this house gives God a central presence and status not uncommon in Ireland at the time. We prayed as a family, like when the Angelus bells struck at noon and six in the evening. We knelt at night to say the Holy Rosary. Many of our rites of passage as children were rooted in Catholicism – our first communion, our confirmation, and so on.

My father, who is 85, would not have seen anything remarkable in this. He was merely carrying on the tradition of his own father’s generation. Having spent half his life working, he recently retired, closing his drapery store. His undertaker’s business continues. For me and others in the family it meant that death was never far away or overtly mysterious. We became accustomed to the dead of our parish being prepared for the final ceremonies before burial. We would often come home from school to see who had died that day.

If we truly wanted to make our father proud, we would have mastered the game he followed all his life: hurling. This ancient Irish sport, requiring great dexterity, courage and speed, can still weave a spell on him. Born in a rural community he has seen his own life change and now that of his children too. In recent years he lost a brother to whom he was close. Now I see him deriving great joy from his grandchildren. In their company he seems tranquil. At peace. His work done.

Though now a more secular society, Ireland still has remnants and relics of the old religious faith, even if many of its devoted followers are typically advanced in age – part of what might be termed a dying generation. The Catholic Church had been one of the country’s mainstays. Falling Mass attendances, declining priest numbers and various damaging scandals have shaken the institution and weakened its grip. Despite this my father is a daily Mass-goer; his faith doesn’t appear to have flinched.

The house where I grew up in the west of Ireland is where my father now resides with his wife and their daughter Susan; all the rest of the family have flown the nest, some starting families of their own, one in New York where she has become part of the Irish Diaspora. The religious paraphernalia located throughout this house gives God a central presence and status not uncommon in Ireland at the time. We prayed as a family, like when the Angelus bells struck at noon and six in the evening. We knelt at night to say the Holy Rosary. Many of our rites of passage as children were rooted in Catholicism – our first communion, our confirmation, and so on.

My father, who is 85, would not have seen anything remarkable in this. He was merely carrying on the tradition of his own father’s generation. Having spent half his life working, he recently retired, closing his drapery store. His undertaker’s business continues. For me and others in the family it meant that death was never far away or overtly mysterious. We became accustomed to the dead of our parish being prepared for the final ceremonies before burial. We would often come home from school to see who had died that day.

If we truly wanted to make our father proud, we would have mastered the game he followed all his life: hurling. This ancient Irish sport, requiring great dexterity, courage and speed, can still weave a spell on him. Born in a rural community he has seen his own life change and now that of his children too. In recent years he lost a brother to whom he was close. Now I see him deriving great joy from his grandchildren. In their company he seems tranquil. At peace. His work done.

Though now a more secular society, Ireland still has remnants and relics of the old religious faith, even if many of its devoted followers are typically advanced in age – part of what might be termed a dying generation. The Catholic Church had been one of the country’s mainstays. Falling Mass attendances, declining priest numbers and various damaging scandals have shaken the institution and weakened its grip. Despite this my father is a daily Mass-goer; his faith doesn’t appear to have flinched.

The house where I grew up in the west of Ireland is where my father now resides with his wife and their daughter Susan; all the rest of the family have flown the nest, some starting families of their own, one in New York where she has become part of the Irish Diaspora. The religious paraphernalia located throughout this house gives God a central presence and status not uncommon in Ireland at the time. We prayed as a family, like when the Angelus bells struck at noon and six in the evening. We knelt at night to say the Holy Rosary. Many of our rites of passage as children were rooted in Catholicism – our first communion, our confirmation, and so on.

My father, who is 85, would not have seen anything remarkable in this. He was merely carrying on the tradition of his own father’s generation. Having spent half his life working, he recently retired, closing his drapery store. His undertaker’s business continues. For me and others in the family it meant that death was never far away or overtly mysterious. We became accustomed to the dead of our parish being prepared for the final ceremonies before burial. We would often come home from school to see who had died that day.

If we truly wanted to make our father proud, we would have mastered the game he followed all his life: hurling. This ancient Irish sport, requiring great dexterity, courage and speed, can still weave a spell on him. Born in a rural community he has seen his own life change and now that of his children too. In recent years he lost a brother to whom he was close. Now I see him deriving great joy from his grandchildren. In their company he seems tranquil. At peace. His work done.

Though now a more secular society, Ireland still has remnants and relics of the old religious faith, even if many of its devoted followers are typically advanced in age – part of what might be termed a dying generation. The Catholic Church had been one of the country’s mainstays. Falling Mass attendances, declining priest numbers and various damaging scandals have shaken the institution and weakened its grip. Despite this my father is a daily Mass-goer; his faith doesn’t appear to have flinched.

The house where I grew up in the west of Ireland is where my father now resides with his wife and their daughter Susan; all the rest of the family have flown the nest, some starting families of their own, one in New York where she has become part of the Irish Diaspora. The religious paraphernalia located throughout this house gives God a central presence and status not uncommon in Ireland at the time. We prayed as a family, like when the Angelus bells struck at noon and six in the evening. We knelt at night to say the Holy Rosary. Many of our rites of passage as children were rooted in Catholicism – our first communion, our confirmation, and so on.

My father, who is 85, would not have seen anything remarkable in this. He was merely carrying on the tradition of his own father’s generation. Having spent half his life working, he recently retired, closing his drapery store. His undertaker’s business continues. For me and others in the family it meant that death was never far away or overtly mysterious. We became accustomed to the dead of our parish being prepared for the final ceremonies before burial. We would often come home from school to see who had died that day.

If we truly wanted to make our father proud, we would have mastered the game he followed all his life: hurling. This ancient Irish sport, requiring great dexterity, courage and speed, can still weave a spell on him. Born in a rural community he has seen his own life change and now that of his children too. In recent years he lost a brother to whom he was close. Now I see him deriving great joy from his grandchildren. In their company he seems tranquil. At peace. His work done.

Though now a more secular society, Ireland still has remnants and relics of the old religious faith, even if many of its devoted followers are typically advanced in age – part of what might be termed a dying generation. The Catholic Church had been one of the country’s mainstays. Falling Mass attendances, declining priest numbers and various damaging scandals have shaken the institution and weakened its grip. Despite this my father is a daily Mass-goer; his faith doesn’t appear to have flinched.

The house where I grew up in the west of Ireland is where my father now resides with his wife and their daughter Susan; all the rest of the family have flown the nest, some starting families of their own, one in New York where she has become part of the Irish Diaspora. The religious paraphernalia located throughout this house gives God a central presence and status not uncommon in Ireland at the time. We prayed as a family, like when the Angelus bells struck at noon and six in the evening. We knelt at night to say the Holy Rosary. Many of our rites of passage as children were rooted in Catholicism – our first communion, our confirmation, and so on.

My father, who is 85, would not have seen anything remarkable in this. He was merely carrying on the tradition of his own father’s generation. Having spent half his life working, he recently retired, closing his drapery store. His undertaker’s business continues. For me and others in the family it meant that death was never far away or overtly mysterious. We became accustomed to the dead of our parish being prepared for the final ceremonies before burial. We would often come home from school to see who had died that day.

If we truly wanted to make our father proud, we would have mastered the game he followed all his life: hurling. This ancient Irish sport, requiring great dexterity, courage and speed, can still weave a spell on him. Born in a rural community he has seen his own life change and now that of his children too. In recent years he lost a brother to whom he was close. Now I see him deriving great joy from his grandchildren. In their company he seems tranquil. At peace. His work done.

Though now a more secular society, Ireland still has remnants and relics of the old religious faith, even if many of its devoted followers are typically advanced in age – part of what might be termed a dying generation. The Catholic Church had been one of the country’s mainstays. Falling Mass attendances, declining priest numbers and various damaging scandals have shaken the institution and weakened its grip. Despite this my father is a daily Mass-goer; his faith doesn’t appear to have flinched.

The house where I grew up in the west of Ireland is where my father now resides with his wife and their daughter Susan; all the rest of the family have flown the nest, some starting families of their own, one in New York where she has become part of the Irish Diaspora. The religious paraphernalia located throughout this house gives God a central presence and status not uncommon in Ireland at the time. We prayed as a family, like when the Angelus bells struck at noon and six in the evening. We knelt at night to say the Holy Rosary. Many of our rites of passage as children were rooted in Catholicism – our first communion, our confirmation, and so on.

My father, who is 85, would not have seen anything remarkable in this. He was merely carrying on the tradition of his own father’s generation. Having spent half his life working, he recently retired, closing his drapery store. His undertaker’s business continues. For me and others in the family it meant that death was never far away or overtly mysterious. We became accustomed to the dead of our parish being prepared for the final ceremonies before burial. We would often come home from school to see who had died that day.

If we truly wanted to make our father proud, we would have mastered the game he followed all his life: hurling. This ancient Irish sport, requiring great dexterity, courage and speed, can still weave a spell on him. Born in a rural community he has seen his own life change and now that of his children too. In recent years he lost a brother to whom he was close. Now I see him deriving great joy from his grandchildren. In their company he seems tranquil. At peace. His work done.

Though now a more secular society, Ireland still has remnants and relics of the old religious faith, even if many of its devoted followers are typically advanced in age – part of what might be termed a dying generation. The Catholic Church had been one of the country’s mainstays. Falling Mass attendances, declining priest numbers and various damaging scandals have shaken the institution and weakened its grip. Despite this my father is a daily Mass-goer; his faith doesn’t appear to have flinched.

The house where I grew up in the west of Ireland is where my father now resides with his wife and their daughter Susan; all the rest of the family have flown the nest, some starting families of their own, one in New York where she has become part of the Irish Diaspora. The religious paraphernalia located throughout this house gives God a central presence and status not uncommon in Ireland at the time. We prayed as a family, like when the Angelus bells struck at noon and six in the evening. We knelt at night to say the Holy Rosary. Many of our rites of passage as children were rooted in Catholicism – our first communion, our confirmation, and so on.

My father, who is 85, would not have seen anything remarkable in this. He was merely carrying on the tradition of his own father’s generation. Having spent half his life working, he recently retired, closing his drapery store. His undertaker’s business continues. For me and others in the family it meant that death was never far away or overtly mysterious. We became accustomed to the dead of our parish being prepared for the final ceremonies before burial. We would often come home from school to see who had died that day.

If we truly wanted to make our father proud, we would have mastered the game he followed all his life: hurling. This ancient Irish sport, requiring great dexterity, courage and speed, can still weave a spell on him. Born in a rural community he has seen his own life change and now that of his children too. In recent years he lost a brother to whom he was close. Now I see him deriving great joy from his grandchildren. In their company he seems tranquil. At peace. His work done.

Though now a more secular society, Ireland still has remnants and relics of the old religious faith, even if many of its devoted followers are typically advanced in age – part of what might be termed a dying generation. The Catholic Church had been one of the country’s mainstays. Falling Mass attendances, declining priest numbers and various damaging scandals have shaken the institution and weakened its grip. Despite this my father is a daily Mass-goer; his faith doesn’t appear to have flinched.

The house where I grew up in the west of Ireland is where my father now resides with his wife and their daughter Susan; all the rest of the family have flown the nest, some starting families of their own, one in New York where she has become part of the Irish Diaspora. The religious paraphernalia located throughout this house gives God a central presence and status not uncommon in Ireland at the time. We prayed as a family, like when the Angelus bells struck at noon and six in the evening. We knelt at night to say the Holy Rosary. Many of our rites of passage as children were rooted in Catholicism – our first communion, our confirmation, and so on.

My father, who is 85, would not have seen anything remarkable in this. He was merely carrying on the tradition of his own father’s generation. Having spent half his life working, he recently retired, closing his drapery store. His undertaker’s business continues. For me and others in the family it meant that death was never far away or overtly mysterious. We became accustomed to the dead of our parish being prepared for the final ceremonies before burial. We would often come home from school to see who had died that day.

If we truly wanted to make our father proud, we would have mastered the game he followed all his life: hurling. This ancient Irish sport, requiring great dexterity, courage and speed, can still weave a spell on him. Born in a rural community he has seen his own life change and now that of his children too. In recent years he lost a brother to whom he was close. Now I see him deriving great joy from his grandchildren. In their company he seems tranquil. At peace. His work done.

Though now a more secular society, Ireland still has remnants and relics of the old religious faith, even if many of its devoted followers are typically advanced in age – part of what might be termed a dying generation. The Catholic Church had been one of the country’s mainstays. Falling Mass attendances, declining priest numbers and various damaging scandals have shaken the institution and weakened its grip. Despite this my father is a daily Mass-goer; his faith doesn’t appear to have flinched.

The house where I grew up in the west of Ireland is where my father now resides with his wife and their daughter Susan; all the rest of the family have flown the nest, some starting families of their own, one in New York where she has become part of the Irish Diaspora. The religious paraphernalia located throughout this house gives God a central presence and status not uncommon in Ireland at the time. We prayed as a family, like when the Angelus bells struck at noon and six in the evening. We knelt at night to say the Holy Rosary. Many of our rites of passage as children were rooted in Catholicism – our first communion, our confirmation, and so on.

My father, who is 85, would not have seen anything remarkable in this. He was merely carrying on the tradition of his own father’s generation. Having spent half his life working, he recently retired, closing his drapery store. His undertaker’s business continues. For me and others in the family it meant that death was never far away or overtly mysterious. We became accustomed to the dead of our parish being prepared for the final ceremonies before burial. We would often come home from school to see who had died that day.

If we truly wanted to make our father proud, we would have mastered the game he followed all his life: hurling. This ancient Irish sport, requiring great dexterity, courage and speed, can still weave a spell on him. Born in a rural community he has seen his own life change and now that of his children too. In recent years he lost a brother to whom he was close. Now I see him deriving great joy from his grandchildren. In their company he seems tranquil. At peace. His work done.

Though now a more secular society, Ireland still has remnants and relics of the old religious faith, even if many of its devoted followers are typically advanced in age – part of what might be termed a dying generation. The Catholic Church had been one of the country’s mainstays. Falling Mass attendances, declining priest numbers and various damaging scandals have shaken the institution and weakened its grip. Despite this my father is a daily Mass-goer; his faith doesn’t appear to have flinched.

The house where I grew up in the west of Ireland is where my father now resides with his wife and their daughter Susan; all the rest of the family have flown the nest, some starting families of their own, one in New York where she has become part of the Irish Diaspora. The religious paraphernalia located throughout this house gives God a central presence and status not uncommon in Ireland at the time. We prayed as a family, like when the Angelus bells struck at noon and six in the evening. We knelt at night to say the Holy Rosary. Many of our rites of passage as children were rooted in Catholicism – our first communion, our confirmation, and so on.

My father, who is 85, would not have seen anything remarkable in this. He was merely carrying on the tradition of his own father’s generation. Having spent half his life working, he recently retired, closing his drapery store. His undertaker’s business continues. For me and others in the family it meant that death was never far away or overtly mysterious. We became accustomed to the dead of our parish being prepared for the final ceremonies before burial. We would often come home from school to see who had died that day.

If we truly wanted to make our father proud, we would have mastered the game he followed all his life: hurling. This ancient Irish sport, requiring great dexterity, courage and speed, can still weave a spell on him. Born in a rural community he has seen his own life change and now that of his children too. In recent years he lost a brother to whom he was close. Now I see him deriving great joy from his grandchildren. In their company he seems tranquil. At peace. His work done.

Though now a more secular society, Ireland still has remnants and relics of the old religious faith, even if many of its devoted followers are typically advanced in age – part of what might be termed a dying generation. The Catholic Church had been one of the country’s mainstays. Falling Mass attendances, declining priest numbers and various damaging scandals have shaken the institution and weakened its grip. Despite this my father is a daily Mass-goer; his faith doesn’t appear to have flinched.

The house where I grew up in the west of Ireland is where my father now resides with his wife and their daughter Susan; all the rest of the family have flown the nest, some starting families of their own, one in New York where she has become part of the Irish Diaspora. The religious paraphernalia located throughout this house gives God a central presence and status not uncommon in Ireland at the time. We prayed as a family, like when the Angelus bells struck at noon and six in the evening. We knelt at night to say the Holy Rosary. Many of our rites of passage as children were rooted in Catholicism – our first communion, our confirmation, and so on.

My father, who is 85, would not have seen anything remarkable in this. He was merely carrying on the tradition of his own father’s generation. Having spent half his life working, he recently retired, closing his drapery store. His undertaker’s business continues. For me and others in the family it meant that death was never far away or overtly mysterious. We became accustomed to the dead of our parish being prepared for the final ceremonies before burial. We would often come home from school to see who had died that day.

If we truly wanted to make our father proud, we would have mastered the game he followed all his life: hurling. This ancient Irish sport, requiring great dexterity, courage and speed, can still weave a spell on him. Born in a rural community he has seen his own life change and now that of his children too. In recent years he lost a brother to whom he was close. Now I see him deriving great joy from his grandchildren. In their company he seems tranquil. At peace. His work done.

Though now a more secular society, Ireland still has remnants and relics of the old religious faith, even if many of its devoted followers are typically advanced in age – part of what might be termed a dying generation. The Catholic Church had been one of the country’s mainstays. Falling Mass attendances, declining priest numbers and various damaging scandals have shaken the institution and weakened its grip. Despite this my father is a daily Mass-goer; his faith doesn’t appear to have flinched.

The house where I grew up in the west of Ireland is where my father now resides with his wife and their daughter Susan; all the rest of the family have flown the nest, some starting families of their own, one in New York where she has become part of the Irish Diaspora. The religious paraphernalia located throughout this house gives God a central presence and status not uncommon in Ireland at the time. We prayed as a family, like when the Angelus bells struck at noon and six in the evening. We knelt at night to say the Holy Rosary. Many of our rites of passage as children were rooted in Catholicism – our first communion, our confirmation, and so on.

My father, who is 85, would not have seen anything remarkable in this. He was merely carrying on the tradition of his own father’s generation. Having spent half his life working, he recently retired, closing his drapery store. His undertaker’s business continues. For me and others in the family it meant that death was never far away or overtly mysterious. We became accustomed to the dead of our parish being prepared for the final ceremonies before burial. We would often come home from school to see who had died that day.

If we truly wanted to make our father proud, we would have mastered the game he followed all his life: hurling. This ancient Irish sport, requiring great dexterity, courage and speed, can still weave a spell on him. Born in a rural community he has seen his own life change and now that of his children too. In recent years he lost a brother to whom he was close. Now I see him deriving great joy from his grandchildren. In their company he seems tranquil. At peace. His work done.

Though now a more secular society, Ireland still has remnants and relics of the old religious faith, even if many of its devoted followers are typically advanced in age – part of what might be termed a dying generation. The Catholic Church had been one of the country’s mainstays. Falling Mass attendances, declining priest numbers and various damaging scandals have shaken the institution and weakened its grip. Despite this my father is a daily Mass-goer; his faith doesn’t appear to have flinched.

The house where I grew up in the west of Ireland is where my father now resides with his wife and their daughter Susan; all the rest of the family have flown the nest, some starting families of their own, one in New York where she has become part of the Irish Diaspora. The religious paraphernalia located throughout this house gives God a central presence and status not uncommon in Ireland at the time. We prayed as a family, like when the Angelus bells struck at noon and six in the evening. We knelt at night to say the Holy Rosary. Many of our rites of passage as children were rooted in Catholicism – our first communion, our confirmation, and so on.

My father, who is 85, would not have seen anything remarkable in this. He was merely carrying on the tradition of his own father’s generation. Having spent half his life working, he recently retired, closing his drapery store. His undertaker’s business continues. For me and others in the family it meant that death was never far away or overtly mysterious. We became accustomed to the dead of our parish being prepared for the final ceremonies before burial. We would often come home from school to see who had died that day.

If we truly wanted to make our father proud, we would have mastered the game he followed all his life: hurling. This ancient Irish sport, requiring great dexterity, courage and speed, can still weave a spell on him. Born in a rural community he has seen his own life change and now that of his children too. In recent years he lost a brother to whom he was close. Now I see him deriving great joy from his grandchildren. In their company he seems tranquil. At peace. His work done.

Though now a more secular society, Ireland still has remnants and relics of the old religious faith, even if many of its devoted followers are typically advanced in age – part of what might be termed a dying generation. The Catholic Church had been one of the country’s mainstays. Falling Mass attendances, declining priest numbers and various damaging scandals have shaken the institution and weakened its grip. Despite this my father is a daily Mass-goer; his faith doesn’t appear to have flinched.

The house where I grew up in the west of Ireland is where my father now resides with his wife and their daughter Susan; all the rest of the family have flown the nest, some starting families of their own, one in New York where she has become part of the Irish Diaspora. The religious paraphernalia located throughout this house gives God a central presence and status not uncommon in Ireland at the time. We prayed as a family, like when the Angelus bells struck at noon and six in the evening. We knelt at night to say the Holy Rosary. Many of our rites of passage as children were rooted in Catholicism – our first communion, our confirmation, and so on.

My father, who is 85, would not have seen anything remarkable in this. He was merely carrying on the tradition of his own father’s generation. Having spent half his life working, he recently retired, closing his drapery store. His undertaker’s business continues. For me and others in the family it meant that death was never far away or overtly mysterious. We became accustomed to the dead of our parish being prepared for the final ceremonies before burial. We would often come home from school to see who had died that day.

If we truly wanted to make our father proud, we would have mastered the game he followed all his life: hurling. This ancient Irish sport, requiring great dexterity, courage and speed, can still weave a spell on him. Born in a rural community he has seen his own life change and now that of his children too. In recent years he lost a brother to whom he was close. Now I see him deriving great joy from his grandchildren. In their company he seems tranquil. At peace. His work done.

Though now a more secular society, Ireland still has remnants and relics of the old religious faith, even if many of its devoted followers are typically advanced in age – part of what might be termed a dying generation. The Catholic Church had been one of the country’s mainstays. Falling Mass attendances, declining priest numbers and various damaging scandals have shaken the institution and weakened its grip. Despite this my father is a daily Mass-goer; his faith doesn’t appear to have flinched.

The house where I grew up in the west of Ireland is where my father now resides with his wife and their daughter Susan; all the rest of the family have flown the nest, some starting families of their own, one in New York where she has become part of the Irish Diaspora. The religious paraphernalia located throughout this house gives God a central presence and status not uncommon in Ireland at the time. We prayed as a family, like when the Angelus bells struck at noon and six in the evening. We knelt at night to say the Holy Rosary. Many of our rites of passage as children were rooted in Catholicism – our first communion, our confirmation, and so on.

My father, who is 85, would not have seen anything remarkable in this. He was merely carrying on the tradition of his own father’s generation. Having spent half his life working, he recently retired, closing his drapery store. His undertaker’s business continues. For me and others in the family it meant that death was never far away or overtly mysterious. We became accustomed to the dead of our parish being prepared for the final ceremonies before burial. We would often come home from school to see who had died that day.

If we truly wanted to make our father proud, we would have mastered the game he followed all his life: hurling. This ancient Irish sport, requiring great dexterity, courage and speed, can still weave a spell on him. Born in a rural community he has seen his own life change and now that of his children too. In recent years he lost a brother to whom he was close. Now I see him deriving great joy from his grandchildren. In their company he seems tranquil. At peace. His work done.

Though now a more secular society, Ireland still has remnants and relics of the old religious faith, even if many of its devoted followers are typically advanced in age – part of what might be termed a dying generation. The Catholic Church had been one of the country’s mainstays. Falling Mass attendances, declining priest numbers and various damaging scandals have shaken the institution and weakened its grip. Despite this my father is a daily Mass-goer; his faith doesn’t appear to have flinched.

The house where I grew up in the west of Ireland is where my father now resides with his wife and their daughter Susan; all the rest of the family have flown the nest, some starting families of their own, one in New York where she has become part of the Irish Diaspora. The religious paraphernalia located throughout this house gives God a central presence and status not uncommon in Ireland at the time. We prayed as a family, like when the Angelus bells struck at noon and six in the evening. We knelt at night to say the Holy Rosary. Many of our rites of passage as children were rooted in Catholicism – our first communion, our confirmation, and so on.

My father, who is 85, would not have seen anything remarkable in this. He was merely carrying on the tradition of his own father’s generation. Having spent half his life working, he recently retired, closing his drapery store. His undertaker’s business continues. For me and others in the family it meant that death was never far away or overtly mysterious. We became accustomed to the dead of our parish being prepared for the final ceremonies before burial. We would often come home from school to see who had died that day.

If we truly wanted to make our father proud, we would have mastered the game he followed all his life: hurling. This ancient Irish sport, requiring great dexterity, courage and speed, can still weave a spell on him. Born in a rural community he has seen his own life change and now that of his children too. In recent years he lost a brother to whom he was close. Now I see him deriving great joy from his grandchildren. In their company he seems tranquil. At peace. His work done.

Though now a more secular society, Ireland still has remnants and relics of the old religious faith, even if many of its devoted followers are typically advanced in age – part of what might be termed a dying generation. The Catholic Church had been one of the country’s mainstays. Falling Mass attendances, declining priest numbers and various damaging scandals have shaken the institution and weakened its grip. Despite this my father is a daily Mass-goer; his faith doesn’t appear to have flinched.

The house where I grew up in the west of Ireland is where my father now resides with his wife and their daughter Susan; all the rest of the family have flown the nest, some starting families of their own, one in New York where she has become part of the Irish Diaspora. The religious paraphernalia located throughout this house gives God a central presence and status not uncommon in Ireland at the time. We prayed as a family, like when the Angelus bells struck at noon and six in the evening. We knelt at night to say the Holy Rosary. Many of our rites of passage as children were rooted in Catholicism – our first communion, our confirmation, and so on.

My father, who is 85, would not have seen anything remarkable in this. He was merely carrying on the tradition of his own father’s generation. Having spent half his life working, he recently retired, closing his drapery store. His undertaker’s business continues. For me and others in the family it meant that death was never far away or overtly mysterious. We became accustomed to the dead of our parish being prepared for the final ceremonies before burial. We would often come home from school to see who had died that day.

If we truly wanted to make our father proud, we would have mastered the game he followed all his life: hurling. This ancient Irish sport, requiring great dexterity, courage and speed, can still weave a spell on him. Born in a rural community he has seen his own life change and now that of his children too. In recent years he lost a brother to whom he was close. Now I see him deriving great joy from his grandchildren. In their company he seems tranquil. At peace. His work done.

Though now a more secular society, Ireland still has remnants and relics of the old religious faith, even if many of its devoted followers are typically advanced in age – part of what might be termed a dying generation. The Catholic Church had been one of the country’s mainstays. Falling Mass attendances, declining priest numbers and various damaging scandals have shaken the institution and weakened its grip. Despite this my father is a daily Mass-goer; his faith doesn’t appear to have flinched.

The house where I grew up in the west of Ireland is where my father now resides with his wife and their daughter Susan; all the rest of the family have flown the nest, some starting families of their own, one in New York where she has become part of the Irish Diaspora. The religious paraphernalia located throughout this house gives God a central presence and status not uncommon in Ireland at the time. We prayed as a family, like when the Angelus bells struck at noon and six in the evening. We knelt at night to say the Holy Rosary. Many of our rites of passage as children were rooted in Catholicism – our first communion, our confirmation, and so on.

My father, who is 85, would not have seen anything remarkable in this. He was merely carrying on the tradition of his own father’s generation. Having spent half his life working, he recently retired, closing his drapery store. His undertaker’s business continues. For me and others in the family it meant that death was never far away or overtly mysterious. We became accustomed to the dead of our parish being prepared for the final ceremonies before burial. We would often come home from school to see who had died that day.

If we truly wanted to make our father proud, we would have mastered the game he followed all his life: hurling. This ancient Irish sport, requiring great dexterity, courage and speed, can still weave a spell on him. Born in a rural community he has seen his own life change and now that of his children too. In recent years he lost a brother to whom he was close. Now I see him deriving great joy from his grandchildren. In their company he seems tranquil. At peace. His work done.

Though now a more secular society, Ireland still has remnants and relics of the old religious faith, even if many of its devoted followers are typically advanced in age – part of what might be termed a dying generation. The Catholic Church had been one of the country’s mainstays. Falling Mass attendances, declining priest numbers and various damaging scandals have shaken the institution and weakened its grip. Despite this my father is a daily Mass-goer; his faith doesn’t appear to have flinched.

The house where I grew up in the west of Ireland is where my father now resides with his wife and their daughter Susan; all the rest of the family have flown the nest, some starting families of their own, one in New York where she has become part of the Irish Diaspora. The religious paraphernalia located throughout this house gives God a central presence and status not uncommon in Ireland at the time. We prayed as a family, like when the Angelus bells struck at noon and six in the evening. We knelt at night to say the Holy Rosary. Many of our rites of passage as children were rooted in Catholicism – our first communion, our confirmation, and so on.

My father, who is 85, would not have seen anything remarkable in this. He was merely carrying on the tradition of his own father’s generation. Having spent half his life working, he recently retired, closing his drapery store. His undertaker’s business continues. For me and others in the family it meant that death was never far away or overtly mysterious. We became accustomed to the dead of our parish being prepared for the final ceremonies before burial. We would often come home from school to see who had died that day.

If we truly wanted to make our father proud, we would have mastered the game he followed all his life: hurling. This ancient Irish sport, requiring great dexterity, courage and speed, can still weave a spell on him. Born in a rural community he has seen his own life change and now that of his children too. In recent years he lost a brother to whom he was close. Now I see him deriving great joy from his grandchildren. In their company he seems tranquil. At peace. His work done.

Though now a more secular society, Ireland still has remnants and relics of the old religious faith, even if many of its devoted followers are typically advanced in age – part of what might be termed a dying generation. The Catholic Church had been one of the country’s mainstays. Falling Mass attendances, declining priest numbers and various damaging scandals have shaken the institution and weakened its grip. Despite this my father is a daily Mass-goer; his faith doesn’t appear to have flinched.

The house where I grew up in the west of Ireland is where my father now resides with his wife and their daughter Susan; all the rest of the family have flown the nest, some starting families of their own, one in New York where she has become part of the Irish Diaspora. The religious paraphernalia located throughout this house gives God a central presence and status not uncommon in Ireland at the time. We prayed as a family, like when the Angelus bells struck at noon and six in the evening. We knelt at night to say the Holy Rosary. Many of our rites of passage as children were rooted in Catholicism – our first communion, our confirmation, and so on.

My father, who is 85, would not have seen anything remarkable in this. He was merely carrying on the tradition of his own father’s generation. Having spent half his life working, he recently retired, closing his drapery store. His undertaker’s business continues. For me and others in the family it meant that death was never far away or overtly mysterious. We became accustomed to the dead of our parish being prepared for the final ceremonies before burial. We would often come home from school to see who had died that day.

If we truly wanted to make our father proud, we would have mastered the game he followed all his life: hurling. This ancient Irish sport, requiring great dexterity, courage and speed, can still weave a spell on him. Born in a rural community he has seen his own life change and now that of his children too. In recent years he lost a brother to whom he was close. Now I see him deriving great joy from his grandchildren. In their company he seems tranquil. At peace. His work done.

Though now a more secular society, Ireland still has remnants and relics of the old religious faith, even if many of its devoted followers are typically advanced in age – part of what might be termed a dying generation. The Catholic Church had been one of the country’s mainstays. Falling Mass attendances, declining priest numbers and various damaging scandals have shaken the institution and weakened its grip. Despite this my father is a daily Mass-goer; his faith doesn’t appear to have flinched.

The house where I grew up in the west of Ireland is where my father now resides with his wife and their daughter Susan; all the rest of the family have flown the nest, some starting families of their own, one in New York where she has become part of the Irish Diaspora. The religious paraphernalia located throughout this house gives God a central presence and status not uncommon in Ireland at the time. We prayed as a family, like when the Angelus bells struck at noon and six in the evening. We knelt at night to say the Holy Rosary. Many of our rites of passage as children were rooted in Catholicism – our first communion, our confirmation, and so on.

My father, who is 85, would not have seen anything remarkable in this. He was merely carrying on the tradition of his own father’s generation. Having spent half his life working, he recently retired, closing his drapery store. His undertaker’s business continues. For me and others in the family it meant that death was never far away or overtly mysterious. We became accustomed to the dead of our parish being prepared for the final ceremonies before burial. We would often come home from school to see who had died that day.

If we truly wanted to make our father proud, we would have mastered the game he followed all his life: hurling. This ancient Irish sport, requiring great dexterity, courage and speed, can still weave a spell on him. Born in a rural community he has seen his own life change and now that of his children too. In recent years he lost a brother to whom he was close. Now I see him deriving great joy from his grandchildren. In their company he seems tranquil. At peace. His work done.

Though now a more secular society, Ireland still has remnants and relics of the old religious faith, even if many of its devoted followers are typically advanced in age – part of what might be termed a dying generation. The Catholic Church had been one of the country’s mainstays. Falling Mass attendances, declining priest numbers and various damaging scandals have shaken the institution and weakened its grip. Despite this my father is a daily Mass-goer; his faith doesn’t appear to have flinched.

The house where I grew up in the west of Ireland is where my father now resides with his wife and their daughter Susan; all the rest of the family have flown the nest, some starting families of their own, one in New York where she has become part of the Irish Diaspora. The religious paraphernalia located throughout this house gives God a central presence and status not uncommon in Ireland at the time. We prayed as a family, like when the Angelus bells struck at noon and six in the evening. We knelt at night to say the Holy Rosary. Many of our rites of passage as children were rooted in Catholicism – our first communion, our confirmation, and so on.

My father, who is 85, would not have seen anything remarkable in this. He was merely carrying on the tradition of his own father’s generation. Having spent half his life working, he recently retired, closing his drapery store. His undertaker’s business continues. For me and others in the family it meant that death was never far away or overtly mysterious. We became accustomed to the dead of our parish being prepared for the final ceremonies before burial. We would often come home from school to see who had died that day.

If we truly wanted to make our father proud, we would have mastered the game he followed all his life: hurling. This ancient Irish sport, requiring great dexterity, courage and speed, can still weave a spell on him. Born in a rural community he has seen his own life change and now that of his children too. In recent years he lost a brother to whom he was close. Now I see him deriving great joy from his grandchildren. In their company he seems tranquil. At peace. His work done.

Though now a more secular society, Ireland still has remnants and relics of the old religious faith, even if many of its devoted followers are typically advanced in age – part of what might be termed a dying generation. The Catholic Church had been one of the country’s mainstays. Falling Mass attendances, declining priest numbers and various damaging scandals have shaken the institution and weakened its grip. Despite this my father is a daily Mass-goer; his faith doesn’t appear to have flinched.

The house where I grew up in the west of Ireland is where my father now resides with his wife and their daughter Susan; all the rest of the family have flown the nest, some starting families of their own, one in New York where she has become part of the Irish Diaspora. The religious paraphernalia located throughout this house gives God a central presence and status not uncommon in Ireland at the time. We prayed as a family, like when the Angelus bells struck at noon and six in the evening. We knelt at night to say the Holy Rosary. Many of our rites of passage as children were rooted in Catholicism – our first communion, our confirmation, and so on.

My father, who is 85, would not have seen anything remarkable in this. He was merely carrying on the tradition of his own father’s generation. Having spent half his life working, he recently retired, closing his drapery store. His undertaker’s business continues. For me and others in the family it meant that death was never far away or overtly mysterious. We became accustomed to the dead of our parish being prepared for the final ceremonies before burial. We would often come home from school to see who had died that day.

If we truly wanted to make our father proud, we would have mastered the game he followed all his life: hurling. This ancient Irish sport, requiring great dexterity, courage and speed, can still weave a spell on him. Born in a rural community he has seen his own life change and now that of his children too. In recent years he lost a brother to whom he was close. Now I see him deriving great joy from his grandchildren. In their company he seems tranquil. At peace. His work done.

Though now a more secular society, Ireland still has remnants and relics of the old religious faith, even if many of its devoted followers are typically advanced in age – part of what might be termed a dying generation. The Catholic Church had been one of the country’s mainstays. Falling Mass attendances, declining priest numbers and various damaging scandals have shaken the institution and weakened its grip. Despite this my father is a daily Mass-goer; his faith doesn’t appear to have flinched.

The house where I grew up in the west of Ireland is where my father now resides with his wife and their daughter Susan; all the rest of the family have flown the nest, some starting families of their own, one in New York where she has become part of the Irish Diaspora. The religious paraphernalia located throughout this house gives God a central presence and status not uncommon in Ireland at the time. We prayed as a family, like when the Angelus bells struck at noon and six in the evening. We knelt at night to say the Holy Rosary. Many of our rites of passage as children were rooted in Catholicism – our first communion, our confirmation, and so on.

My father, who is 85, would not have seen anything remarkable in this. He was merely carrying on the tradition of his own father’s generation. Having spent half his life working, he recently retired, closing his drapery store. His undertaker’s business continues. For me and others in the family it meant that death was never far away or overtly mysterious. We became accustomed to the dead of our parish being prepared for the final ceremonies before burial. We would often come home from school to see who had died that day.

If we truly wanted to make our father proud, we would have mastered the game he followed all his life: hurling. This ancient Irish sport, requiring great dexterity, courage and speed, can still weave a spell on him. Born in a rural community he has seen his own life change and now that of his children too. In recent years he lost a brother to whom he was close. Now I see him deriving great joy from his grandchildren. In their company he seems tranquil. At peace. His work done.

Though now a more secular society, Ireland still has remnants and relics of the old religious faith, even if many of its devoted followers are typically advanced in age – part of what might be termed a dying generation. The Catholic Church had been one of the country’s mainstays. Falling Mass attendances, declining priest numbers and various damaging scandals have shaken the institution and weakened its grip. Despite this my father is a daily Mass-goer; his faith doesn’t appear to have flinched.

The house where I grew up in the west of Ireland is where my father now resides with his wife and their daughter Susan; all the rest of the family have flown the nest, some starting families of their own, one in New York where she has become part of the Irish Diaspora. The religious paraphernalia located throughout this house gives God a central presence and status not uncommon in Ireland at the time. We prayed as a family, like when the Angelus bells struck at noon and six in the evening. We knelt at night to say the Holy Rosary. Many of our rites of passage as children were rooted in Catholicism – our first communion, our confirmation, and so on.

My father, who is 85, would not have seen anything remarkable in this. He was merely carrying on the tradition of his own father’s generation. Having spent half his life working, he recently retired, closing his drapery store. His undertaker’s business continues. For me and others in the family it meant that death was never far away or overtly mysterious. We became accustomed to the dead of our parish being prepared for the final ceremonies before burial. We would often come home from school to see who had died that day.

If we truly wanted to make our father proud, we would have mastered the game he followed all his life: hurling. This ancient Irish sport, requiring great dexterity, courage and speed, can still weave a spell on him. Born in a rural community he has seen his own life change and now that of his children too. In recent years he lost a brother to whom he was close. Now I see him deriving great joy from his grandchildren. In their company he seems tranquil. At peace. His work done.

Though now a more secular society, Ireland still has remnants and relics of the old religious faith, even if many of its devoted followers are typically advanced in age – part of what might be termed a dying generation. The Catholic Church had been one of the country’s mainstays. Falling Mass attendances, declining priest numbers and various damaging scandals have shaken the institution and weakened its grip. Despite this my father is a daily Mass-goer; his faith doesn’t appear to have flinched.

The house where I grew up in the west of Ireland is where my father now resides with his wife and their daughter Susan; all the rest of the family have flown the nest, some starting families of their own, one in New York where she has become part of the Irish Diaspora. The religious paraphernalia located throughout this house gives God a central presence and status not uncommon in Ireland at the time. We prayed as a family, like when the Angelus bells struck at noon and six in the evening. We knelt at night to say the Holy Rosary. Many of our rites of passage as children were rooted in Catholicism – our first communion, our confirmation, and so on.

My father, who is 85, would not have seen anything remarkable in this. He was merely carrying on the tradition of his own father’s generation. Having spent half his life working, he recently retired, closing his drapery store. His undertaker’s business continues. For me and others in the family it meant that death was never far away or overtly mysterious. We became accustomed to the dead of our parish being prepared for the final ceremonies before burial. We would often come home from school to see who had died that day.

If we truly wanted to make our father proud, we would have mastered the game he followed all his life: hurling. This ancient Irish sport, requiring great dexterity, courage and speed, can still weave a spell on him. Born in a rural community he has seen his own life change and now that of his children too. In recent years he lost a brother to whom he was close. Now I see him deriving great joy from his grandchildren. In their company he seems tranquil. At peace. His work done.

Though now a more secular society, Ireland still has remnants and relics of the old religious faith, even if many of its devoted followers are typically advanced in age – part of what might be termed a dying generation. The Catholic Church had been one of the country’s mainstays. Falling Mass attendances, declining priest numbers and various damaging scandals have shaken the institution and weakened its grip. Despite this my father is a daily Mass-goer; his faith doesn’t appear to have flinched.

The house where I grew up in the west of Ireland is where my father now resides with his wife and their daughter Susan; all the rest of the family have flown the nest, some starting families of their own, one in New York where she has become part of the Irish Diaspora. The religious paraphernalia located throughout this house gives God a central presence and status not uncommon in Ireland at the time. We prayed as a family, like when the Angelus bells struck at noon and six in the evening. We knelt at night to say the Holy Rosary. Many of our rites of passage as children were rooted in Catholicism – our first communion, our confirmation, and so on.